Denmark bets on Bovaer to dodge the world’s first cow-methane tax. Then a quarter of farms using it started reporting diarrhea, crashing milk yields, and dead cattle—and now the European Commission wants answers.

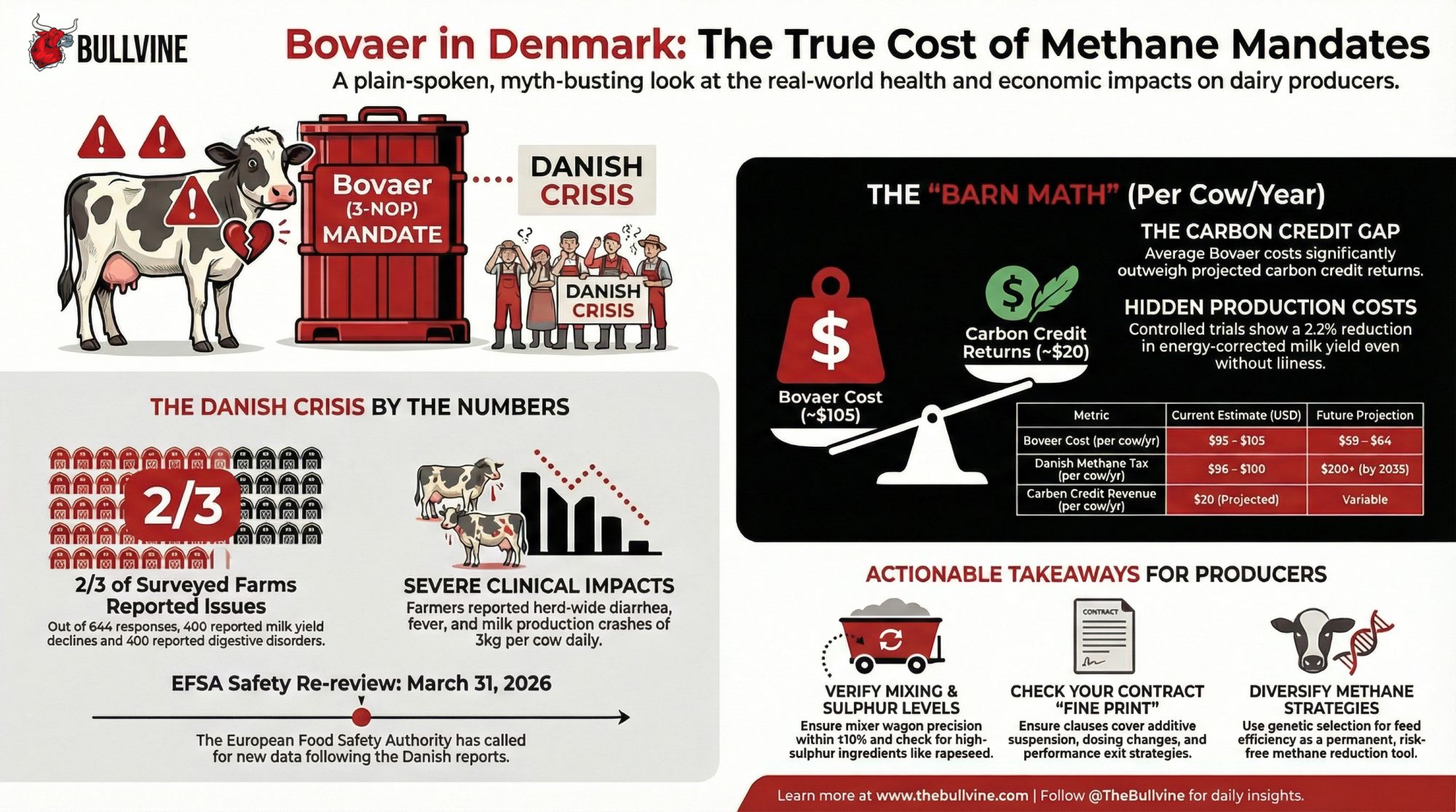

Executive Summary: Denmark told 1,600 dairy farms to feed Bovaer or face fines. Most started in October 2025. By November, SEGES Innovation surveys showed two-thirds of responding farms reporting crashed milk yields, reduced intake, and digestive disorders — diarrhea, fever, and cows that couldn’t stand. Norway and Sweden didn’t wait: both countries paused Bovaer trials entirely. Now the European Commission has ordered EFSA to reassess safety, with a data deadline of March 31, 2026. The question isn’t whether Bovaer is dangerous — it’s whether Denmark’s mandate pushed adoption faster than any protocol could handle, and what that means for North American farms that are now being offered the same additive in methane contracts. Inside: the barn math, four hypotheses nobody else is separating, and the three contract clauses to read before you sign.

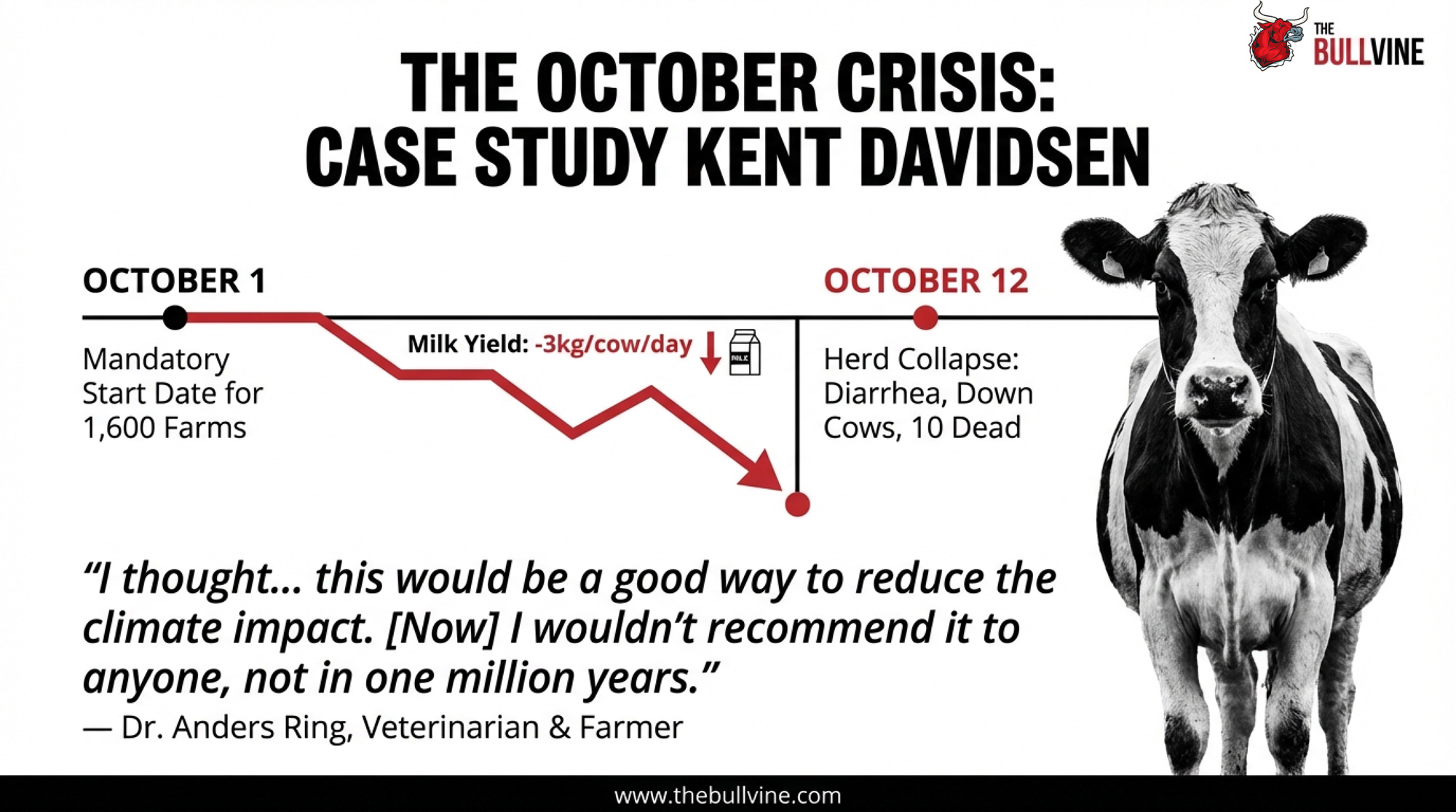

Kent Davidsen started feeding Bovaer to his 1,000-cow herd in Jutland, Denmark, last October — and unlike many of his neighbors, he’d been looking forward to it. Solar panels already covered his barn roofs. He’d voluntarily cut his carbon footprint. As he told Undark Magazine, “I thought to myself that this would be a good way to reduce the climate impact of producing milk”.

Soon after, his entire herd had diarrhea. Milk production dropped by almost 3 kg per cow per day. After 10 to 12 days, some cows couldn’t stand. Within a month, 10 were dead.

“It’s not normal for a full herd of a thousand cows to have diarrhea, all of them,” Davidsen said. He stopped Bovaer on November 4. His cows recovered almost immediately. A month later, milk production was back to pre-Bovaer levels.

Davidsen isn’t alone. He’s one of hundreds.

434 Farms, One Survey, and the Numbers Nobody Expected

Denmark has approximately 1,600 conventional dairy farms milking more than 50 cows. Starting in 2025, those farms were required to feed Bovaer — a methane-reducing additive made by dsm-firmenich containing the active ingredient 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) — for at least 80 days per year, or switch to a high-fat diet. Organic herds got an exemption. Non-compliance risked fines of up to 10,000 DKK, roughly $1,450 USD.

About 75% of farms waited until the October 1 cutoff to start, according to dsm-firmenich itself. The reports started flooding in within weeks.

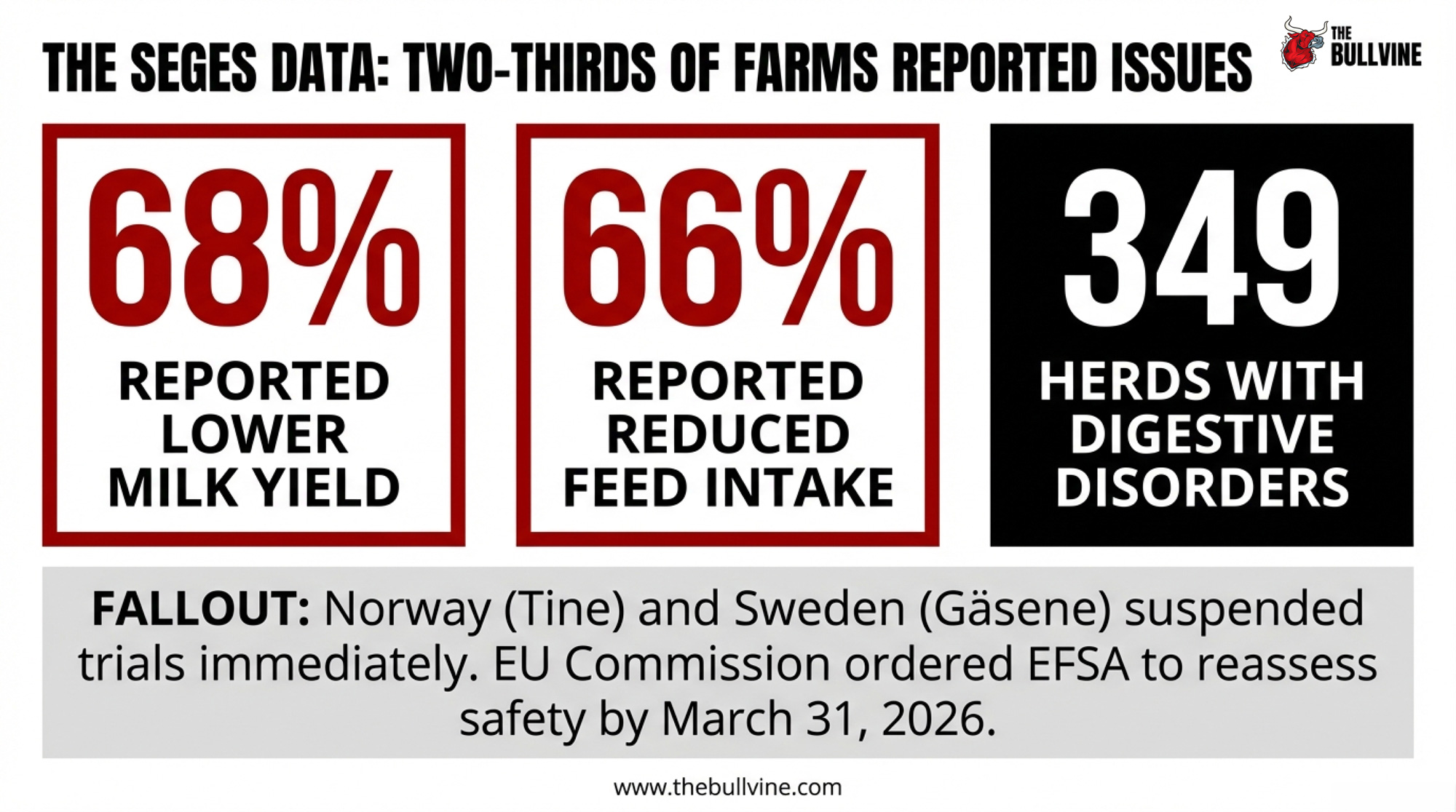

SEGES Innovation, the independent Danish agricultural research body, surveyed those farms. Two snapshots tell the story. A mid-November survey drew 644 responses:

- 434 reported a decline in milk yield

- 419 reported reduced feed intake

- 410 reported digestive and metabolic disorders

- 376 reported both reduced feed intake AND lower milk production

A separate SEGES tally of 551 respondents found 68% reporting lower milk yield, 66% reporting reduced feed intake, and 59% experiencing both, plus 349 herds noting increased digestive and metabolic disorders, including diarrhea, reduced rumination, atypical milk fever, and fever.

Two-thirds of responding farms flagged problems. Clinical signs ranged from diarrhea, fever, and weakness to mastitis, high somatic cell counts, and — in cases like Davidsen’s — animals that couldn’t stand and animals that died. On November 24, the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration clarified that farmers are exempt from feeding Bovaer if their cows get sick. Norway and Sweden didn’t wait for Denmark to sort it out — both countries paused their Bovaer trials entirely. Norway’s largest dairy supplier, Tine, suspended use after multiple reports of collapsing cows. In Sweden, dairy producer Gäsene ended its Bovaer project.

In early February 2026, the European Commission mandated EFSA — the European Food Safety Authority — to deliver a new scientific opinion on whether Bovaer still meets safety conditions for dairy cows. On February 3, EFSA published a public call for data from farms, research institutions, and national authorities, with a submission deadline of March 31, 2026. The same authority that issued a favorable safety opinion on 3-NOP in 2021 — leading to EU market authorization in February 2022 — is now being asked to take another look.

Danish Food Minister Jacob Jensen acknowledged farmers were “reporting challenges” in connection with Bovaer use. And Ida Storm, director of the Danish Agriculture and Food Council for Cattle, didn’t sugarcoat the surprise: “Animal welfare must not be compromised. At the same time, we are surprised, since no research or large-scale trials have indicated problems”.

How Denmark Backed 1,600 Farms Into a Corner

To understand how this happened, you need to understand the policy machinery behind it.

Denmark is committed to cutting national greenhouse gas emissions 70% below 1990 levels by 2030. Agriculture accounts for a significant and growing share of the country’s total carbon output — in part because other sectors have decarbonized faster. In June 2024, the government finalized what it called the Agreement on a Green Denmark, including the world’s first livestock carbon tax, to start in 2030.

The actual tax math matters because the headline number is misleading. On paper, the rate starts at 300 Danish krone (~$43 USD) per metric ton of CO₂ equivalent in 2030, rising to 750 DKK (~$107) by 2035. But a 60% basic deduction applies to average emissions from different livestock types, giving climate-efficient farmers an economic advantage. After that deduction, Danish farmers will actually pay 120 DKK (~$17 USD) per ton in 2030 and 300 DKK (~$43 USD) per ton in 2035.

Danish Dairy Farmers’ Association chairman Kjartan Poulsen estimated the effective cost at roughly 672 krone — about $100 per cow per year starting in 2030, as he told Brownfield Ag News. Other outlets reported the same 672 DKK figure as $96 using the June 2024 exchange rate; Poulsen’s own rounded figure in his July 2024 Brownfield interview was $100. Either way, that’s real money. But it’s quite a bit less than the €130/cow figure floating in some industry reports, which doesn’t account for the 60% deduction. Poulsen told Brownfield that, between deductions and climate-smart practices, “Most will get out of this without paying.”

But the government didn’t wait until 2030. It required emissions-reducing feeding changes starting in 2025 — and farms that didn’t comply faced fines. The vast majority chose Bovaer. And then came October.

Is Bovaer Safe for Dairy Cows?

That’s the question the EFSA review is supposed to answer. The honest answer right now: the data is pulling in different directions, and pretending otherwise doesn’t help you make a good decision.

What the science says: EFSA’s 2021 safety opinion drew on more than a decade of research. dsm-firmenich cites over 55 peer-reviewed published studies since that original approval, and more than 150 studies total to date. Bovaer is authorized in over 70 countries and commercially active in more than 25. A Penn State meta-analysis found it reduces enteric methane by roughly 30% in dairy cows, with no significant effect on feed intake or milk yield, and a tendency to increase milkfat by about 0.2 lb per day. The FDA completed its own multi-year review and approved Bovaer for U.S. dairy cattle in May 2024. Canada’s CFIA approved it in January 2024.

Charles Nicholson of Penn State told AFP that the changes documented in studies “do not seem large enough to reflect or result in other health issues, at least for the average cow”. Luiz Ferraretto at the University of Wisconsin-Madison said, “has been tested extensively worldwide and no concerns about major reductions in dairy cow productivity or health were raised.”

A six-month FrieslandCampina pilot in the Netherlands — 200,000 cows across 158 farms — reported an average 28% reduction in methane emissions, resulting in a 10,000-ton reduction in CO₂e. Participating farmers said adding Bovaer “did not result in changes to animal health or milk production and composition”.

One wrinkle worth noting: a 2025 Aarhus University feeding trial published in the Journal of Dairy Science found that Bovaer supplementation reduced dry matter intake by 1.1 kg/day (a 5.0% reduction) and energy-corrected milk yield by 0.8 kg/day (a 2.2% reduction) — with early-lactation cows showing a larger production decline than mid-to-late-lactation cows. That’s a controlled trial, not a commercial farm. But it suggests the “no effect on production” message from the meta-analysis may be more nuanced than the marketing implies.

What the farms say: Dr. Anders Ring milks roughly 580 cows near the town of Gredstedbro on Denmark’s southern coast. He’s a veterinarian—and he trusts the science. “I’m a veterinarian. I trust the science,” he told Farmers Forum. So when problems started two weeks into feeding Bovaer, he pulled it for two weeks, then tried again. Same problems. He tried a half dose. Same problems.

“I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone, not in one million years,” Ring said. “Just don’t do it”.

Ring reported an explosion of digital dermatitis, from bandaging one to three cows a month to a new case every single day. Two days after he stopped feeding Bovaer, the hoof infections ended. He told Farmers Guardian separately that since stopping, “cow health showed huge signs of improvement” and somatic cell counts “fell by more than 20%” within two days. He didn’t mince words with them either: “In my opinion, Bovaer is a poison”.

Henrik Jensen, a Jutland dairyman with 120 cows, described a similar pattern through citizen journalist Kent Nielsen’s viral video, as reported by Farmers Forum: he pulled Bovaer when his herd fell ill, saw recovery within days, and reported symptoms returning when he reintroduced the additive to meet the mandate’s 80-day requirement. Søren Larsen, a farmer on the island of Funen, reported losing two cows to neurological distress and described a swift recovery when he withdrew the additive, but worse inflammation when he re-dosed. “Our herds are experiments now,” Larsen said.

Charlotte Lauridsen, who heads the Department of Animal and Veterinary Sciences at Aarhus University, told the BBC: “The pattern of disease now being described in the media — with fever, diarrhea and, in some cases, dead cows — has never been observed in our extensive studies”.

That gap — between controlled trials and hundreds of field reports — is exactly what makes this so hard to sort out. Aarhus University has launched a dedicated 2025–2028 research project — the first designed specifically to investigate whether Bovaer affects cow welfare. Professor Margit Bak Jensen, who leads it, said: “Several factors can cause reduced appetite and feed intake, and it can be a sign of discomfort. Therefore, there is reason to investigate whether Bovaer has a negative impact on animal welfare”. Her team will track cows’ activity, lying behavior, and comfort behavior, and test whether dairy cows actively avoid feed with Bovaer when given the choice.

Four Hypotheses Nobody Else Is Separating

Every outlet covering this story frames it as “EFSA reviewing Bovaer.” True. But not useful unless you understand the competing explanations the review needs to sort out.

Could the Product Itself Be the Problem?

The simplest explanation: 3-NOP at commercial dosing causes health problems in some cow populations. If true, those 70-plus country approvals need revisiting. Jan Dijkstra, associate professor in ruminant nutrition at Wageningen University, says the biological mechanism for the reported disease pattern — fever, infection-like symptoms — “is simply not there” based on current science. But hundreds of farm reports are hard to dismiss entirely.

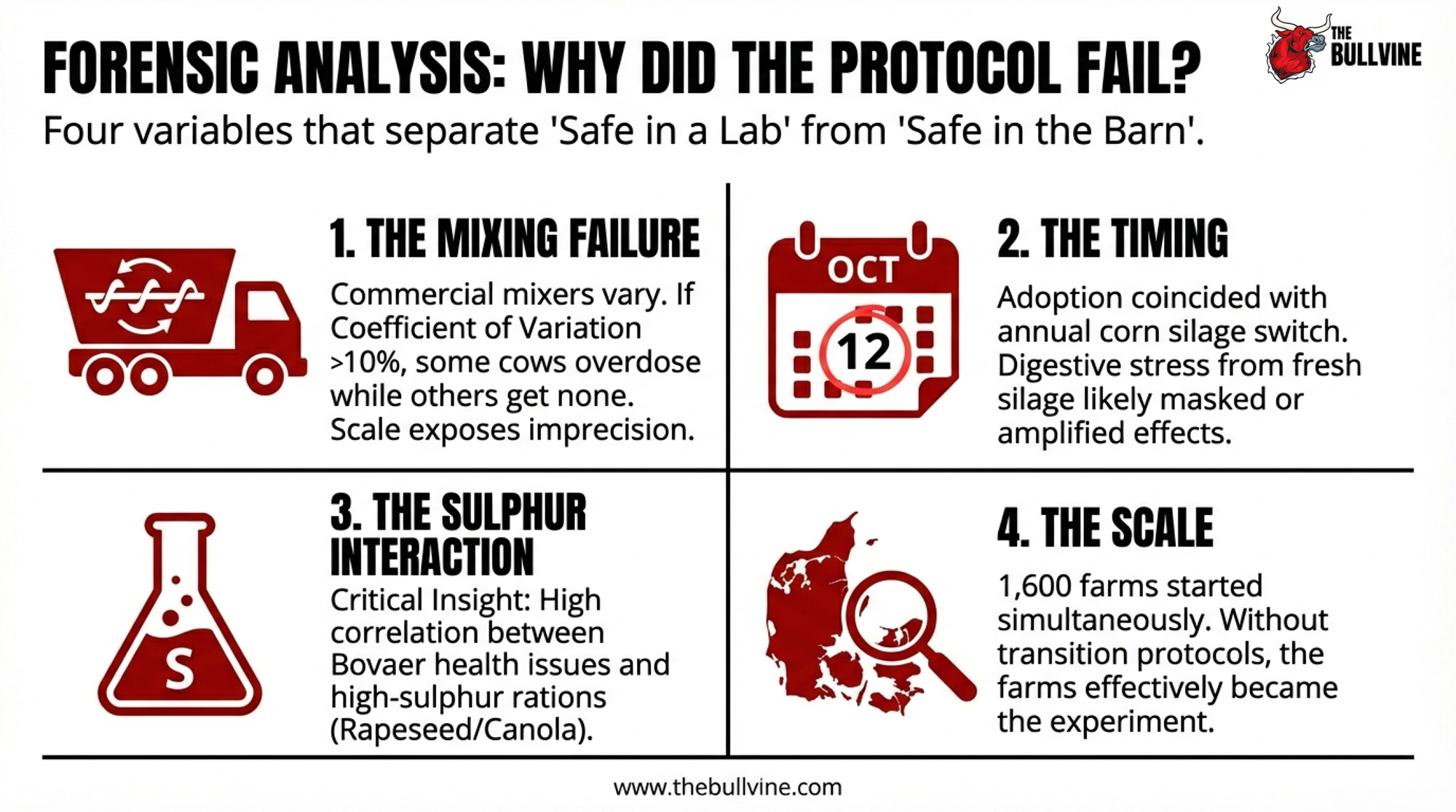

Was It a Mixing and Management Failure?

Lars Arne Hjort Nielsen, senior specialist in cattle production at SEGES Innovation, flagged this directly: “Bovaer must be mixed thoroughly and evenly in the feed ration to avoid overdosing and ensure effectiveness”. On a commercial farm, the mixer wagon does its best with the equipment it’s got. If some cows get double or triple the intended dose while others get none, you’d see exactly the pattern Denmark reported. Ring disagrees—he says his mixing accuracy is 98%, yet he still had problems. Many farms reported mitigating issues by gradually introducing Bovaer, reducing the dose, or stopping entirely.

Did the Timing Create a False Signal?

Dijkstra raised this one: most Danish farms started Bovaer at exactly the same time they made their annual switch to new corn silage. dsm-firmenich pointed out that October is “the most problematic time of the year for routine health problems in dairy herds”. If that silage was unstabilized or carried unwanted bacteria, it could produce digestive problems that look identical to what’s being blamed on Bovaer.

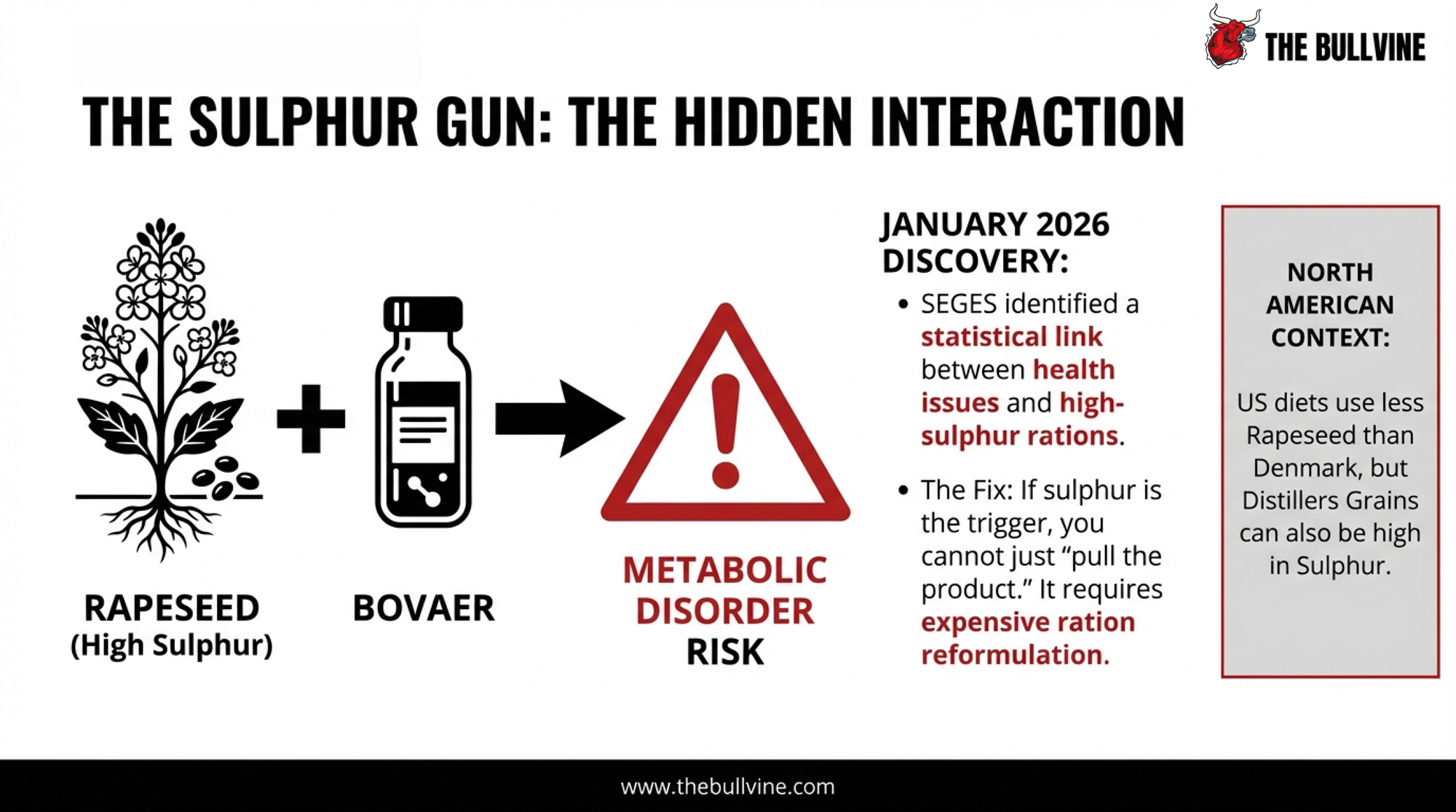

And Then There’s the Sulphur Nobody Tested For

This is the newest — and arguably most important — piece. In January 2026, SEGES data analysis identified a statistical link between Bovaer and high sulphur content in feed rations, indicating an increased risk of metabolic disorders. Rapeseed — common in Danish dairy diets but far less prevalent in North American rations — is a significant sulphur source. Aarhus University announced feeding trials specifically investigating this Bovaer-sulphur interaction, with results expected later in 2026.

If sulphur turns out to be the primary trigger, the fix isn’t pulling Bovaer—it’s reformulating rations to reduce the sulphur load when Bovaer is in the mix. That’s a fundamentally different problem than “the product is dangerous.”

| Hypothesis | What It Means | Risk Indicators for Your Farm | What to Check Now |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Toxicity (3-NOP itself) | Bovaer at commercial doses causes health problems in some cow populations | Any farm feeding Bovaer, regardless of ration or management | Monitor for reduced intake, diarrhea, fever, clinical signs within 2 weeks of starting |

| Mixing/Dosing Failure | Inconsistent mixer precision causes some cows to get 2–3× intended dose | Farms with older TMR equipment, high coefficient of variation (>10%) | Audit mixer wagon accuracy; verify dosing consistency across pens |

| Timing Coincidence (Silage Transition) | October silage changeover masked real cause of digestive problems | Farms that started Bovaer simultaneously with new corn silage harvest | Review silage fermentation quality; test for mycotoxins, unstable pH |

| Sulphur-Bovaer Interaction | High sulphur in rations (rapeseed, canola) triggers metabolic disorders when combined with Bovaer | Farms using rapeseed, canola meal, or high-sulphur forages | Ration analysis: check total dietary sulphur content |

Here’s the thing, though. These four possibilities don’t cancel each other out. They stack. A product that’s safe under laboratory conditions, mixed imprecisely in commercial settings, introduced simultaneously with a silage change, into rations high in sulphur from rapeseed, across 1,600 farms with no transition protocol — that combination would never show up in a peer-reviewed trial. It only shows up at scale.

The Barn Math: Methane Tax vs. Bovaer vs. Your Bottom Line

Now let’s put numbers on this for a 300-cow herd. Because this is where your decision actually lives.

Denmark’s effective methane tax (starting 2030): After the 60% deduction, Danish cows will cost their owners about $96–$100 per head per year, based on the standard 672 DKK calculation. On 300 cows, that’s approximately $29,000–$30,000/year. By 2035, the effective rate more than doubles — the gross rate jumps to 750 DKK/ton with the same 60% deduction.

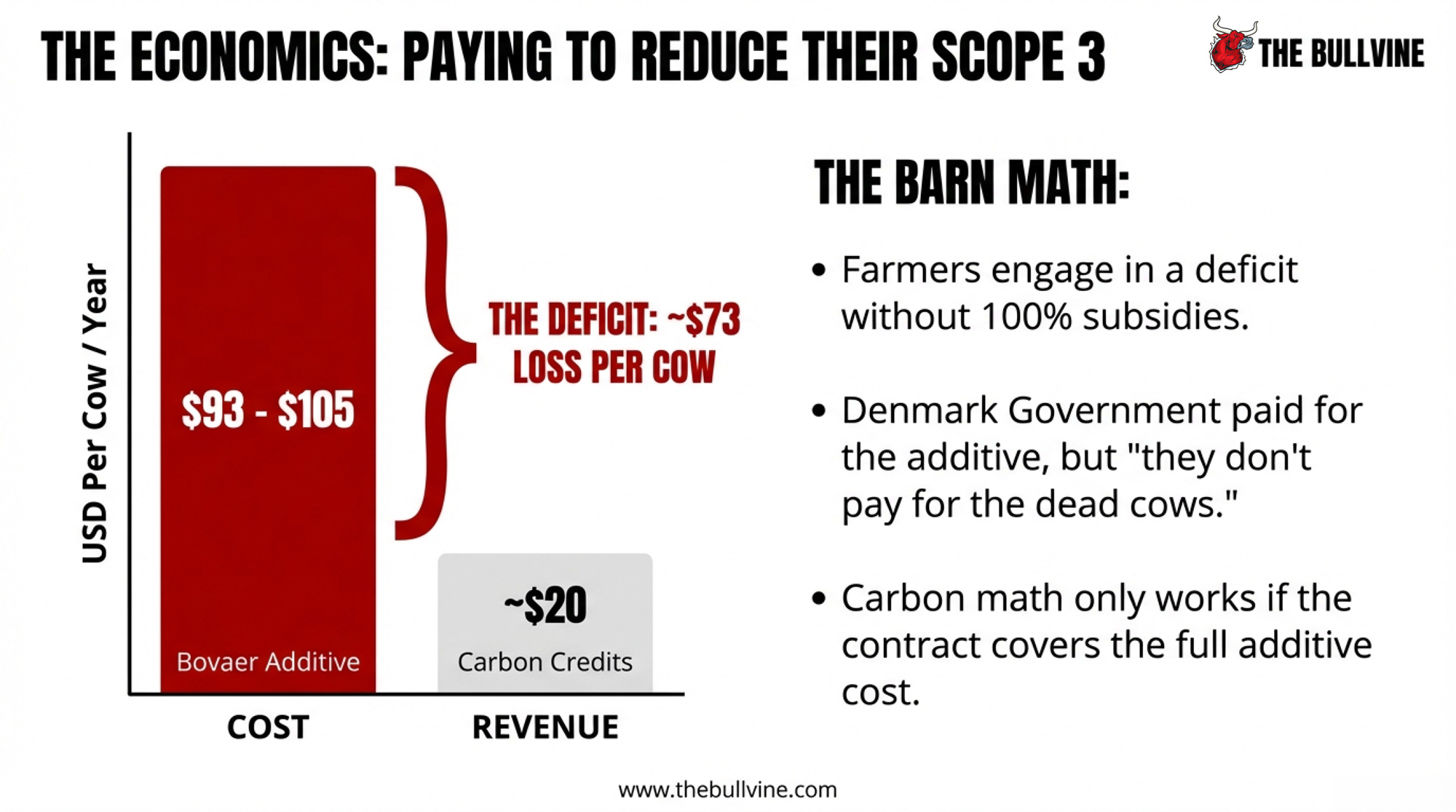

Bovaer’s feed cost: DSM-Firmenich senior marketing director Julien Martin pegged the cost at roughly 1 cent per litre of milk, or about $93–$105 per cow annually in U.S. dollars. Construction of a new manufacturing plant in Dalry, Scotland — slated for completion in 2025 — was projected to reduce costs to approximately $58–$64 per cow per year. dsm-firmenich VP of Bovaer Mark van Nieuwland told Dairy Global the cost in European terms was €80–€90/cow/year, with a projected drop to €50–€55 as manufacturing scales up. Elanco, which holds the U.S. distribution rights, has described the cost as “a few cents a gallon of milk”.

On a 300-cow herd at the current $93–$105/cow range, you’re looking at $27,900–$31,500/year in additive cost alone. Not nothing. But not the apocalypse, either —if it works as advertised. At the projected post-Scotland-plant pricing of $58–$64/cow, that drops to $17,400–$19,200/year. The Danish government currently pays for the additive itself — “but they don’t pay for the dead cows,” as Ring put it.

The hidden cost nobody modeled: What happens when two-thirds of surveyed farms report milk yield declines? On Davidsen’s 1,000-cow herd, a drop of almost three kilos per cow per day means roughly 3,000 kg of lost milk daily. Even a two-week disruption at Danish farmgate prices represents significant economic damage — before you count vet bills, dead animals, or the production lag after recovery. And the Aarhus University trial suggests a 2.2% ECM reduction even under controlled conditions, which on a 300-cow herd averaging 35 kg ECM/day, pencils out to roughly 230 kg of lost production daily. That’s not a health crisis. But it’s a cost that doesn’t appear in any marketing brochure.

North American carbon credit math: Elanco’s carbon credit platform, Athian, announced in November 2025 that it had facilitated $18 million in payments to farmers since 2024 for emissions-reducing practices, including feed ingredients and alternative manure management — coinciding with the close of a $4 million Series A funding round. In September 2025, Athian announced its first verified carbon credit sale to Dairy Farmers of America, based on reductions from Texas dairy farmer Jasper DeVos — nearly 1,150 metric tons of CO₂e avoided. Elanco’s Katie Cook, VP of Farm Animal Health, projects a potential return of “$20 or more per lactating cow” per year through carbon markets and USDA conservation programs, and over the long term, “more than $200 million of value for the U.S. dairy industry” if the entire industry adopted enteric methane interventions.

So here’s your per-cow math. On your 300-cow herd: you’d spend roughly $28,000–$31,500 on Bovaer at today’s pricing to generate maybe $6,000 in carbon credits at Elanco’s projected $20/cow. That’s a big gap. And it’s the gap between what the farmer gets paid and what the corporate buyer values those credits at that deserves its own article

| Cost/Revenue Item | Per Cow (Current) | 300-Cow Herd (Current) | Per Cow (Future) | 300-Cow Herd (Future) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovaer Additive Cost | $93 – $105 | $27,900 – $31,500 | $58 – $64 | $17,400 – $19,200 |

| Carbon Credit Revenue (Projected) | $20 | $6,000 | $20 | $6,000 |

| Danish Methane Tax (If Adopted) | $96 – $100 | $28,800 – $30,000 | $200+ (by 2035) | $60,000+ |

| Net Cost to Farmer (Current Economics) | −$73 to −$85 | −$21,900 to −$25,500 | −$38 to −$44 | −$11,400 to −$13,200 |

One important caveat: that $20/cow figure is Elanco’s projected return, not a guaranteed market price. Actual per-cow revenue depends on what buyers will pay per ton of CO₂e, which varies by contract and marketplace. The math right now: you’d spend substantially more on Bovaer than you’d generate in carbon credits. That only works if somebody else is subsidizing the additive — which is exactly what Denmark did, and exactly the model North American contracts need to replicate for the economics to pencil out for the farmer.

| Metric | Current Estimate (USD) | Future Projection (Post-2025/26) |

| Bovaer Cost (per cow/yr) | $93 – $105 | $58 – $64 |

| Danish Methane Tax (per cow/yr) | $96 – $100 | $200+ (by 2035) |

| Carbon Credit Revenue (per cow/yr) | $20 (Projected) | Variable |

| Net Gap (Cost to Farmer) | ($73 – $85) | ($38 – $44) |

What Does the EFSA Review Mean for North American Farms?

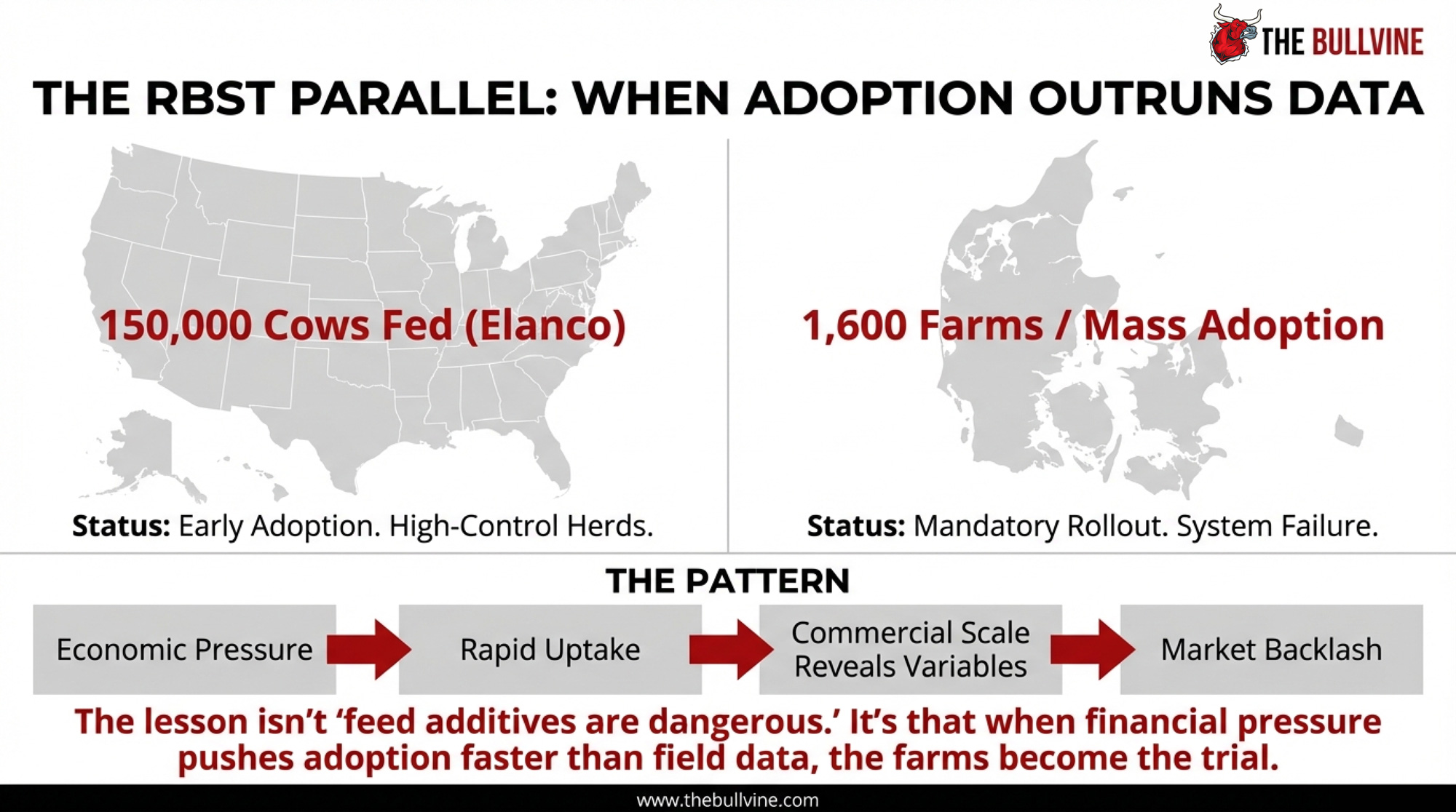

Elanco holds North American distribution rights for Bovaer. Through the end of 2025, the company reported feeding the additive to more than 150,000 U.S. lactating dairy cows, with a farmer retention rate above 90%. Elanco stated it “has not seen the types of issues that are being reported in Denmark”.

That’s worth taking at face value — for now. The U.S. feeding context is genuinely different. American dairies typically run more precise TMR mixing equipment and work closely with nutritionists. Ration profiles differ too: Danish diets include substantially more rapeseed than typical North American formulations, which matters a great deal if the sulphur hypothesis holds up.

But 150,000 cows is a fraction of the 9.4-million-cow U.S. dairy herd. Denmark’s problems surfaced during a mandatory, large-scale, simultaneous commercial adoption — approximately 1,600 farms, diverse management systems, and real-world conditions, all starting at once. The U.S. hasn’t done that yet. And the economic pressure to add another per-cow cost is something you should understand before anyone puts a contract in front of you.

In Canada, Bovaer was approved by CFIA in January 2024. But according to Dairy Farmers of Canada’s chief research officer, Fawn Jackson, “To our knowledge, 3-NOP is not currently being sold to farmers to be used commercially in Canada.” The key Canadian research was a two-year Alberta study with 15,000 beef cattle supported by Emissions Reduction Alberta, in which dsm-firmenich reported peak methane reductions of up to 82%. That headline figure deserves context — the established meta-analysis average is roughly 30% for dairy and 36–45% for beef under typical conditions. The 82% likely reflects peak reductions under specific high-dose beef-feedlot protocols, not what you’d expect in a commercial dairy TMR. Stuart Boeve, chair of Alberta Milk, told the Manitoba Co-operator that even at 50 cents per cow per day, the cost wouldn’t “break the bank for most dairy producers”.

If you’re being offered a methane-credit contract that requires Bovaer, the Danish situation boils down to this: the product’s safety profile at controlled doses is well-documented. Its safety profile under mandatory, rapid, large-scale commercial adoption — with variable mixing precision, diverse rations, and no universal transition protocol — is what just came into question. Those are two very different things.

The rBST Pattern: When Adoption Outruns Data

Dairy farmers over 40 remember this cycle. rBST was approved by the FDA in 1993, supported by strong clinical trial data. Adoption surged because the economics looked obvious. Then came reported complications. Consumer backlash followed. The FDA never withdrew its safety approval, but the market moved anyway. Today, the majority of U.S. milk is marketed rBST-free.

Nobody’s saying Bovaer is rBST. The products are different. The mechanism is different. The science is different.

But the adoption pattern rhymes. Economics drove rapid uptake. Long-term commercial-scale data lagged behind the adoption curve. And the first large-scale mandatory rollout — Denmark — revealed problems the controlled trials didn’t predict. The lesson isn’t “feed additives are dangerous.” It’s this: when financial or regulatory pressure pushes adoption faster than independent field data can accumulate, the farms become the trial.

Ring told Farmers Forum that Danish farmers won’t comply with the 80-day Bovaer mandate again. “They simply won’t feed it to their cows,” he said — adding that they’d flush it down the toilet rather than give it to their herds.

Options and Trade-Offs for Farmers

If you’re currently feeding Bovaer in the U.S. or Canada, don’t panic and pull it based on Danish headlines alone. Elanco’s North American data doesn’t show the same pattern. But do this within 30 days: pull your feeding protocol documentation and verify dosing precision with your nutritionist. Check the coefficient of variation for your mixer wagon. If you can’t confirm consistent dosing within ±10% across every pen, you’ve got the same exposure Denmark had. Also, check your ration’s sulphur content — SEGES flagged that combination specifically. If you’re running rapeseed or other high-sulphur ingredients alongside Bovaer, that conversation with your nutritionist shouldn’t wait. A phone call costs nothing. A herd-wide feed management review pays for itself even without the Bovaer question.

If you’re considering a methane-credit contract that requires Bovaer: Wait for EFSA’s scientific opinion before signing. The data submission deadline is March 31, 2026, and the opinion will follow. That’s not anti-science—it’s risk management. And the straight economics deserve a hard look: at $93–$105/cow/year in additive cost versus a projected $20/cow in carbon credit return, the math only works if the contract subsidizes the additive. If it doesn’t, you’re absorbing the gap for the privilege of reducing someone else’s Scope 3 emissions. Read the fine print.

If EFSA identifies a sulphur-interaction issue, Bovaer is likely to re-enter the conversation quickly — but with ration-specific restrictions that will complicate adoption and potentially increase per-cow feeding costs. If the review flags a broader safety concern, the North American regulatory timeline could reset. Either way, the contracts being offered today probably don’t account for either scenario.

If you want a methane-reduction strategy that doesn’t depend on a single additive: Build the portfolio. Genetic selection for feed efficiency — Feed Saved, Residual Feed Intake — delivers permanent, heritable methane reduction with zero additive risk. Feed management optimization reduces emissions AND costs. Manure management and RNG can generate standalone revenue. The farms that diversify their methane strategy will have greater contract leverage and less exposure than farms that bet on a single product.

Key Takeaways

- If you’re feeding Bovaer now, verify two things this month: your mixer wagon’s dosing consistency and your ration’s sulphur load. Those are the two most controllable risk factors identified in the Danish data.

- If someone offers you a methane contract requiring Bovaer before EFSA publishes its review, look for three clauses: what happens if the additive gets suspended, who pays if dosing protocols change, and what’s your exit if performance falls short. If those clauses aren’t there, the contract isn’t protecting you.

- Run the straight economics before you run the carbon math. Current Bovaer costs run $93–$105/cow/year — roughly five times the $20/cow projected carbon credit return. Know who fills that gap before you sign.

- EFSA’s data call closes March 31, 2026. Watch that date. What comes after it will shape the methane-contract landscape for every dairy farmer in North America.

The Bottom Line

Kent Davidsen said something after the whole ordeal that should sit with you if you’re weighing a methane commitment. After watching his cows crash and recover, after testifying before the Danish parliament, and after losing 10 animals, he started buying organic milk for his family. “It’s a pity,” he said, “when you’re a farmer, and you can’t even buy your own product”.

No evidence has linked Bovaer to any milk or meat safety issue for consumers — EFSA’s 2021 opinion specifically addressed that. Davidsen’s reaction reflects a loss of trust in the regulatory process, not a food-safety finding. But trust is currency in this business.

EFSA’s data deadline is March 31. Your methane contract can wait until the science catches up. Check your ration. Check your contracts. And check what happened when Denmark’s mandate first hit the wall.

Next in The Methane Math series: What your methane contract actually says in the fine print — and the three clauses your lawyer should read twice.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Bovaer Warning: How Denmark’s Methane Mandate Went from Law to Crisis in 6 Weeks – Arm yourself with a 30-day monitoring checklist and specific health exit triggers. This field-tested protocol reveals exactly when to pull the plug to protect herd health before clinical issues crash your production and bottom line.

- The Carbon Credit Conversation: What’s Really Happening on Dairy Farms Today – Exposes the widening gap between $20 commodity credits and $120 premium payouts. Deliver a smarter long-term strategy by identifying which 2026 tax credits pay you directly without locking your operation into predatory, low-value corporate contracts.

- THE METHANE MISDIRECTION: Why The Industry’s Obsession with Feed Additives Is Costing You Money While Genetics Offers the Real Solution – Breaks down how permanent, cumulative genetic gains deliver 30% methane reductions without the perpetual daily additive bill. Arm your operation with a generation-skipping strategy that turns environmental compliance into a permanent, heritable profit center.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!