£368m. Record milk. Arla and Müller aren’t betting on every UK herd. They’re sorting. Which side are you on?

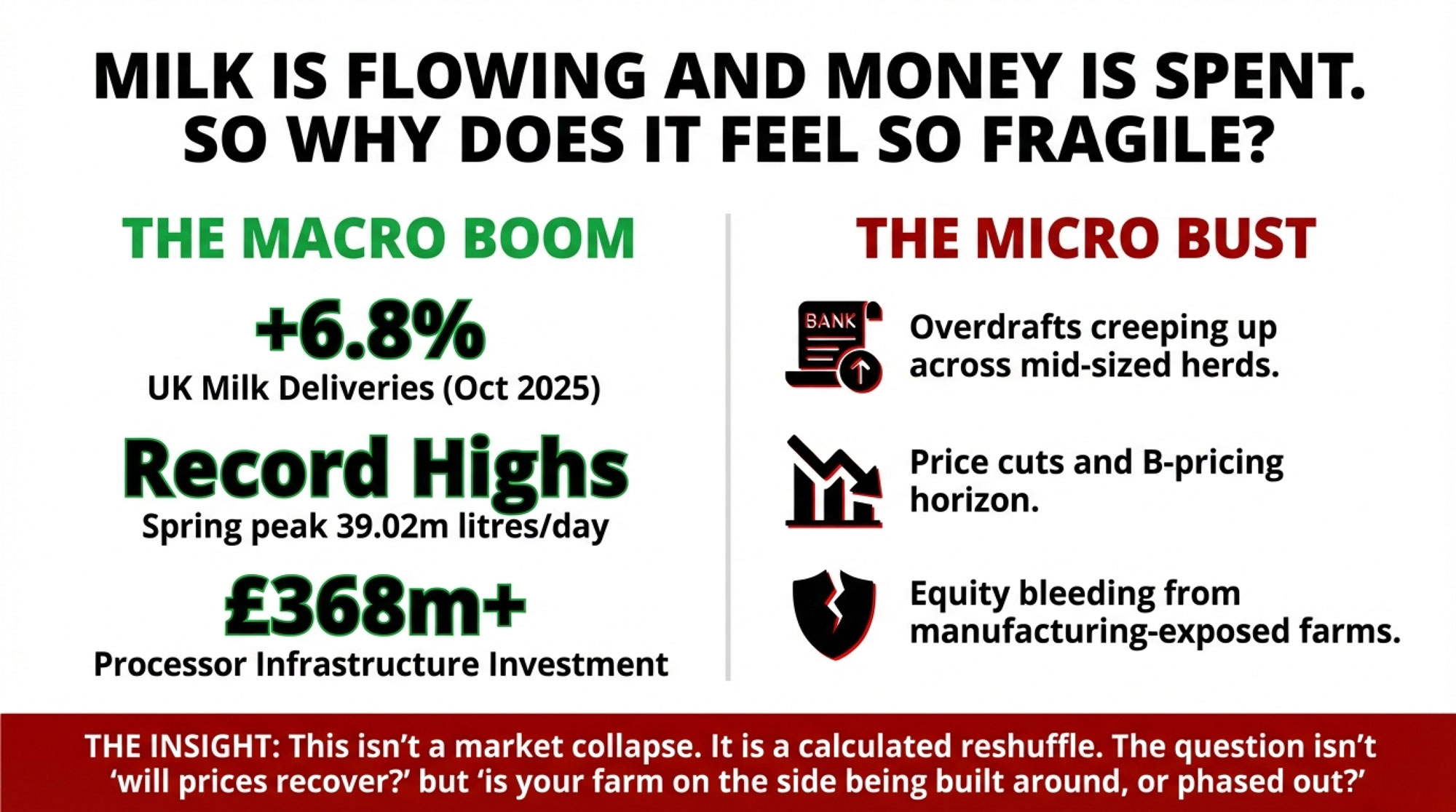

Executive Summary: Here’s what’s really going on in UK dairy: AHDB data shows milk deliveries up 6.8% to 1,309m litres in October 2025, while Arla and Müller are pouring more than £368m into new mozzarella and powder capacity. On the surface, a 20‑year‑high milk‑to‑feed ratio looks like a green light to push litres, but once you price in full labour, power, and interest that’s doubled since the robot boom, many 150–350 cow herds on commodity contracts are losing money on every extra litre. The article shows how processors are quietly sorting suppliers into scale‑efficient, aligned herds they’ll build around and mid‑sized, manufacturing‑exposed herds that either have to reposition or risk being phased out. It breaks down a 90‑day playbook built around IOFC‑based culling, turning feed into a known number, and having a blunt pre‑flush conversation with your buyer about volume and long‑term fit. For Group B herds, it also maps out a realistic “third way” that doesn’t require 800 cows: selective direct‑to‑consumer sales, high‑component or breed‑based premiums, tapping sustainability payments, or, for the right systems, organic conversion. The bottom line is simple: this isn’t another “ride it out” dip like 2016—it’s the moment to decide whether you’re scaling, repositioning, or exiting while you still control the timing.

Here’s what’s really going on in UK dairy right now. On one side of the kitchen table, you’ve got 200–300 cow herds watching the overdraft creep up and wondering how many more price cuts they can swallow. On the other hand, Arla and Müller are investing more than £350 million in UK processing plants over the next few years.

And here’s what’s interesting—AHDB’s October 2025 milk deliveries report shows UK volumes up 6.8% year-on-year to about 1,309 million litres, with GB deliveries also hitting new records. Spring 2025 set a fresh daily peak at 39.02 million litres on 4 May, according to AHDB data, the highest volume on record. The Q4 2025 review now puts the GB forecast for the 2025/26 season at 13.05 billion litres, up 4.9% on the previous year and another record.

So the milk is flowing harder than ever, processors are pouring concrete and stainless steel into British sites… and yet many farms feel more fragile, not less.

That doesn’t look like a collapse to me. It looks like a reshuffle. And the real question—if we’re honest about it—isn’t “will prices recover?” It’s this:

Is your farm on the side of UK dairy that those investments are being built around—or on the side that’s quietly being phased out?

Let’s dig into why that matters, and what you can actually do about it.

At a Glance: What You Need to Know

- The Numbers:

UK milk deliveries up 6.8% to 1,309m litres in October 2025; GB daily average 42.2m litres; Q4 forecast for 2025/26 at 13.05bn litres—a record, according to AHDB. - The Investment:

Arla’s £179m mozzarella plant at Taw Valley plus more than £300m into five UK sites; Müller’s £45m upgrade at Skelmersdale to boost powder capacity by 30%. - The Timeline:

New capacity starts producing around 2027; the squeeze from extra milk and limited capacity is happening now through 2026. - Your 90-Day Moves:

Use the IOFC ranking to cull for cash flow and contract fit, lock 60–75% of spring feed spend, and have a blunt volume-and-contract-fit conversation with your buyer before the flush. - The Big Fork in the Road:

Scale into Group A, reposition into a “third way” niche, or exit on your terms—because just hanging on and hoping won’t fix a structural margin problem.

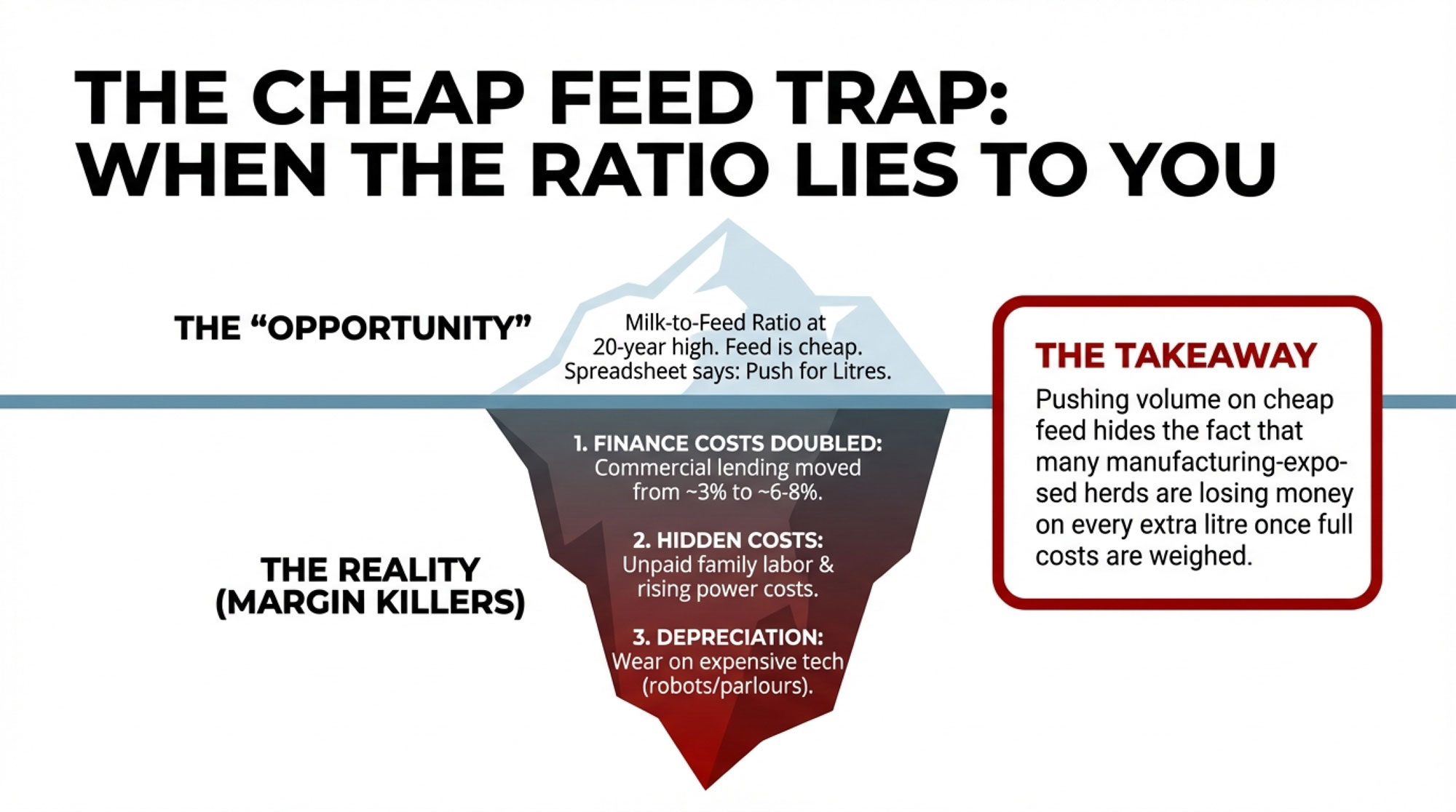

The Cheap Feed Trap: When the Milk-to-Feed Ratio Lies to You

Looking at this trend, it’s easy to see why some herds are tempted to push. AHDB’s Q4 2025 dairy market review highlights that feed costs have eased, and lead dairy analyst Susie Stannard has been clear: the milk-to-feed price ratio is at an almost 20-year high. Feed relative to milk hasn’t looked this “good” since the early 2000s.

On paper, that screams opportunity. Cheaper concentrates against a mid-30s ppl milk price? Every spreadsheet says:

- Turn the taps up.

- Squeeze a bit more from the ration.

- Carry a few extra late-lactation cows.

And at the cow level, that can make sense. If your fresh cow management is solid and your butterfat and protein are holding, extra litres look like extra margin.

The catch is, you’re not the only one reading that ratio.

AHDB’s daily deliveries data show that by October 2025, UK daily milk averaged about 42.2 million litres, up from roughly 39.5 million litres a year earlier—a 6.8% jump. GB volumes are up around 6.7% and have surpassed previous records. The Q4 review projects GB production for 2025/26 at 13.05bn litres, up 4.9% on the year and the highest on record.

All that extra milk is hitting a processing system that, short-term, hasn’t grown by 6–7%. Plants don’t just stretch because the grass came in right.

So what happens?

- More milk is pushed into lower-value commodity powders and cheeses.

- Over-contract litres slide into B-pricing.

- Processors warn about penalties or caps on what they can take in the flush.

Meanwhile, because the milk-to-feed ratio still looks “good,” some herds convince themselves they’re fine—until the full cost-of-production picture lands. That’s where the ratio lies to you.

If you only look at feed and milk price, you miss:

- Labour, including your own hours and unpaid family time.

- Power, parlour running costs, and maintenance.

- Depreciation on parlours, robots, cubicles, and machinery.

- Finance costs, which hurt a lot more when commercial farm lending has moved from around 3% to 6–8%.

Cheap feed keeps marginal litres flowing even when the whole-farm margin is negative. It’s a trap because it keeps structurally unprofitable production alive just long enough to do real damage.

| Herd Size / Scenario | Feed | Labour (incl. family) | Power/Parlour | Depreciation & Repairs | Finance (Interest) | Total CoP | Typical Milk Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150-Cow, Commodity | 8 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 45 | 32 |

| 250-Cow, Commodity | 7 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 36 | 32 |

| 400-Cow, Aligned/Retail | 7 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 29 | 40 |

What Arla and Müller Are Saying With £368 Million

While you’re wrestling with whether to push on the ration, the processors are quietly making their own long-term calls—and they’re speaking very clearly with their capital spend.

Arla’s mozzarella bet and UK spend

In April 2024, Arla Foods UK announced a £179m investment at Taw Valley Creamery in Devon to build a new mozzarella plant. The brief was clear: Arla wants to be a serious player in global mozzarella and foodservice markets, using British milk as the feedstock. Ground was broken in early 2025, and trade coverage indicates production is expected to start by 2027.

On top of that, in May 2024, Arla confirmed more than £300m of investment across five UK sites, including Lockerbie, Stourton, Aylesbury, and Westbury, to upgrade capacity and efficiency. That’s not “keeping the lights on” money. That’s a long-haul bet that UK milk will underpin profitable cheese and ingredient sales for years.

Müller’s powder play at Skelmersdale

Müller’s move is different but rhymes with Arla’s strategy. In July 2025, Müller confirmed a £45m investment in its Skelmersdale site in West Lancashire. The plan outlined in their press release is to increase milk drying capacity by about 30% and ramp up the export of milk powders made in Britain. The goal is to establish Skelmersdale as a flagship drying hub and a major exporter.

Put it together, and you’ve got well north of £368m committed to UK processing capacity, with a clear tilt toward value-added products and exports.

The timing tells its own story

Here’s the bit that’s easy to miss when you’re flat-out on the yard.

- Taw Valley’s mozzarella plant is expected to start producing around 2027, not next month.

- The impact of Skelmersdale’s added drying capacity rolls out over the next couple of years, not in a single step.

So the shape looks like this:

- Now through 2026: Milk deliveries are already up strongly, capacity is tight, and the pain from B-pricing and penalties lands on the wrong herds.

- From 2027 onwards: New stainless comes online and needs milk—but not indiscriminately, and not from every farm currently shipping.

Processors aren’t betting on “UK dairy” as a single homogeneous block. They’re betting on a particular subset of UK dairy that fits the supply profile they’re designing around.

Two Industries Wearing One “UK Dairy” Label

What producers are finding is that “UK dairy” has quietly split into two very different games, even though everyone is under the same headline milk price.

Let’s put some shape around those games.

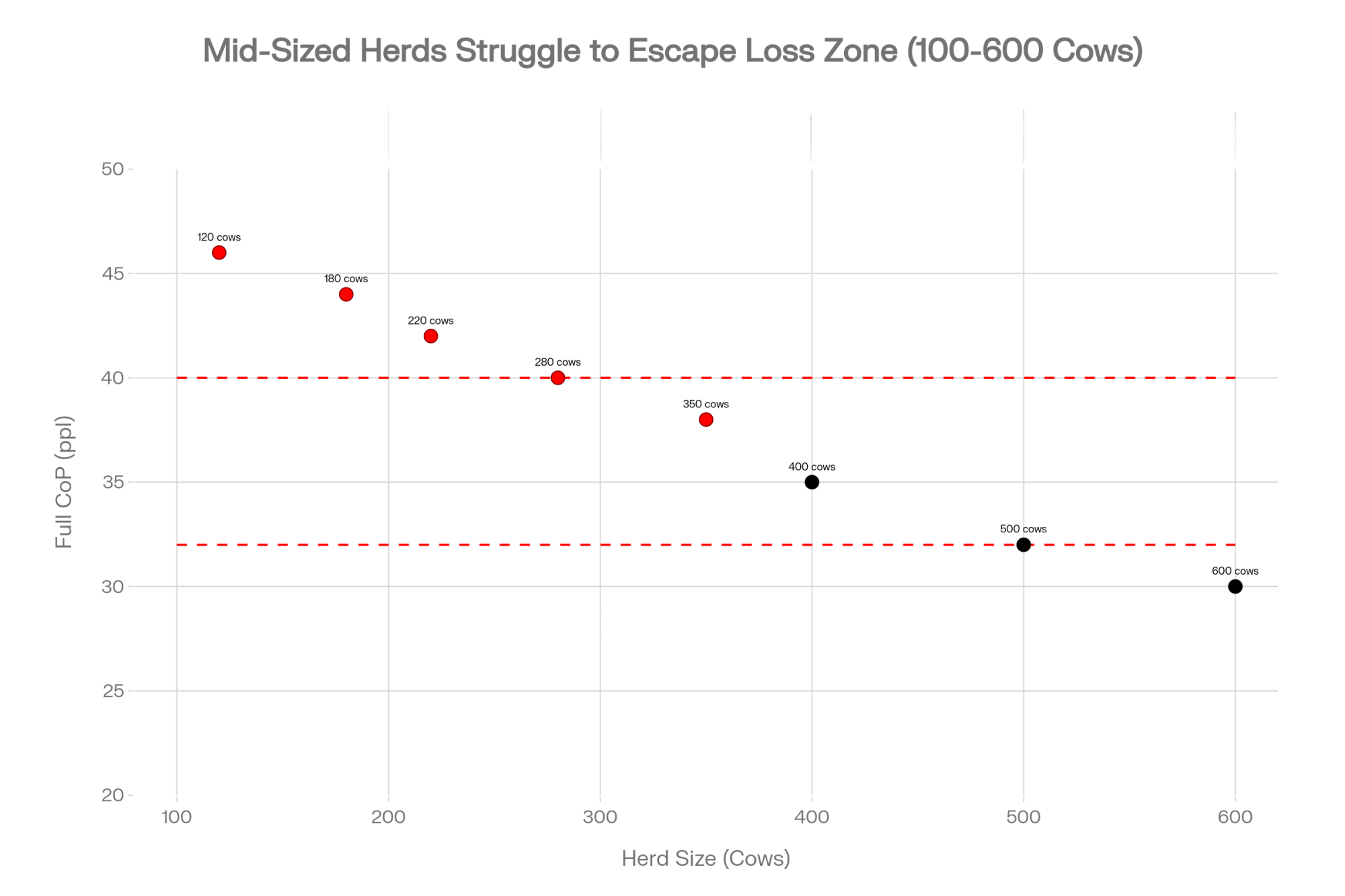

Group A: Scale-efficient, aligned suppliers

This is the group around which those big investments quietly build. Generally:

- Herd size: 400–800 cows, sometimes more.

- Contracts: Retail-aligned supermarket pools, strong co-op deals with sustainability or quality bonuses, or fixed/floored price agreements.

- Cost-of-production: Kingshay’s 2025 Dairy Costings work and AHDB benchmarking both show that top-quartile larger herds often incur full costs—including labour, power, finance, and depreciation—at low-to-mid 30s ppl.

- Real-world margin: On 38–42 ppl aligned or premium contracts, these herds can still generate several ppl of positive margin, especially with strong butterfat performance and bonuses stacked on.

These farms can deliver the volume, consistency, and environmental performance that new plants like Taw Valley and an upgraded Skelmersdale will depend on.

Group B: Mid-sized, commodity-exposed herds

On the other side, you’ve got the mid-sized herds a lot of us grew up with:

- Herd size: Typically 150–350 cows.

- Contracts: Manufacturing/commodity cheese or powder contracts, sometimes with spot exposure and much weaker leverage.

- Cost-of-production: Once you cost in proper family labour and realistic finance charges, many sit well into the 40s ppl on recent GB costings, especially where land is rented, or infrastructure is older.

- Real-world margin: At 32–36 ppl manufacturing prices, that’s a 6–10 ppl gap between revenue and full cost. That difference is coming straight out of equity.

| Metric | Group A (Scale/Aligned) | Group B (Commodity/Mid-Size) |

| Typical Herd Size | 400–800+ | 150–350 |

| Contract Focus | Retail/Aligned/Co-op Premium | Manufacturing/Spot/Commodity |

| Cost of Prod. (ppl) | Low-to-mid 30s | Low-to-mid 40s |

| Primary Goal | Scaling & Efficiency | Repositioning or Transition |

Across UK costings datasets, the swing between bottom- and top-quartile cost of production is often 10–15 ppl for herds in the same size band. Layer contract differences on top, and the net margin gap between Group A and Group B can easily stretch 15–20 ppl.

Same country. Same weather. Same processor names on the cheque. Completely different business reality.

| Metric | Group A: Scale/Aligned | Group B: Commodity/Mid-Size | Margin Gap (ppl) | Processor Bet? |

| Typical Herd Size | 400–800+ cows | 150–350 cows | — | — |

| Primary Contract Type | Retail/Aligned/Co-op Premium | Manufacturing/Commodity/Spot | — | — |

| Cost of Production (ppl) | Low-to-mid 30s (32–36) | Low-to-mid 40s (40–46) | 8–14 ppl gap | Yes |

| Typical Milk Price (ppl) | 38–42 (premium/retail pools) | 30–36 (commodity manufacturing) | — | No |

| Real Margin per Litre (ppl) | +4 to +8 ppl | -6 to -10 ppl | 10–18 ppl gap | — |

| Processor Investment Focus | Core tier (Taw Valley, Skelmersdale planned expansion) | Gradual phase-out or B-pricing squeeze | — | 100% / 0% |

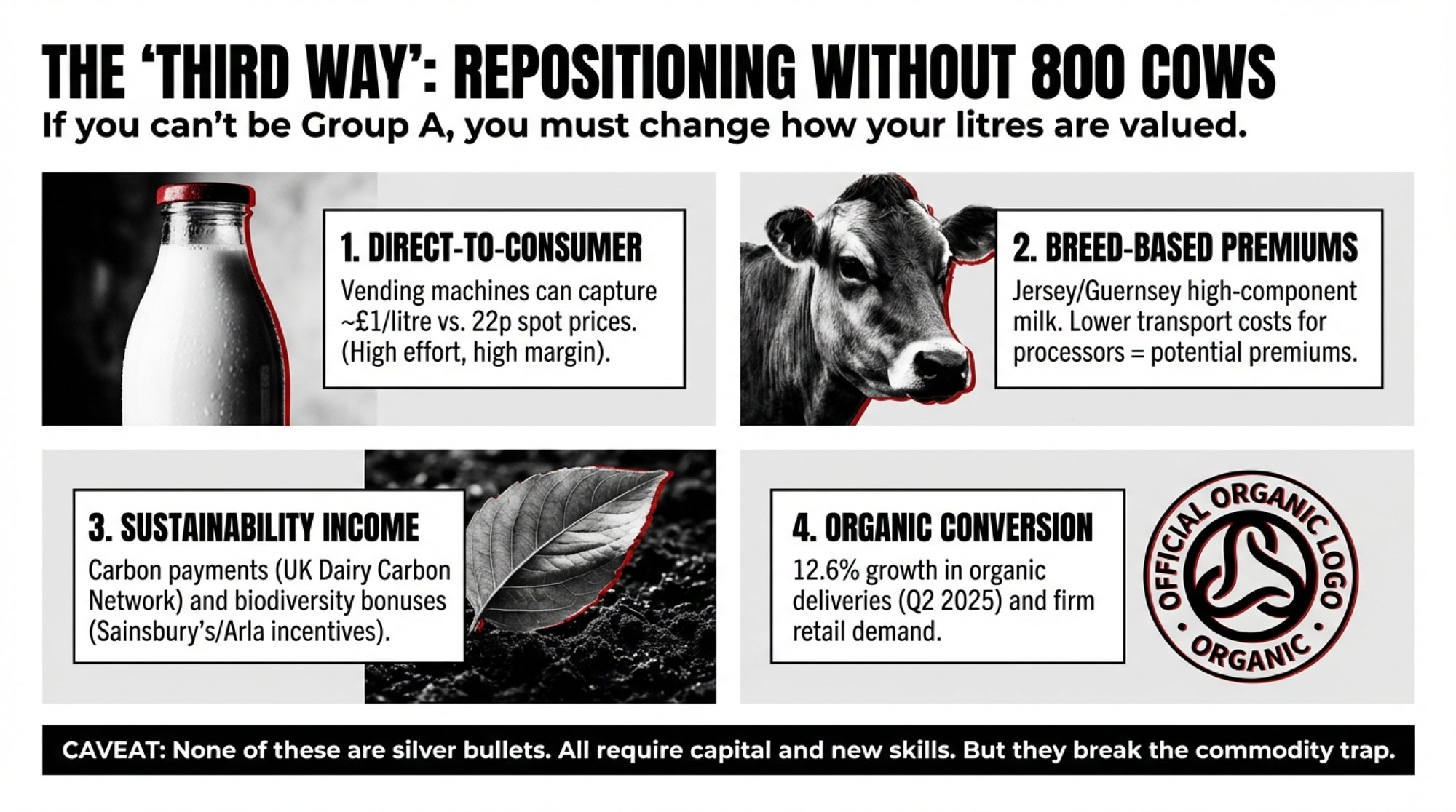

The third way: Repositioning paths that don’t require 800 cows

Before any Group B herd concludes the only choices are “go big or get out,” it’s worth looking at a few verifiedrepositioning paths that some mid-sized farms are using to escape the worst of the commodity trap without turning into 800-cow units.

1. Direct-to-consumer and milk vending.

Dairy Global has been tracking UK dairy farms using on-farm milk vending machines and notes that some operations are achieving around £1 per litre at the machine, compared with roughly 22p per litre from their processor for the same milk. Agriland recently profiled neighbouring farmers in the UK who joined forces to sell direct to the public—one example had around 5% of production sold as raw milk via vending, with the rest processed and sold through their own on-farm plant. It’s not a model for every postcode—footfall, hygiene, compliance, and time are all real hurdles—but for farms near towns, service stations, or tourist routes, turning even a slice of the tank into £1/litre sales completely changes the margin on those litres.

2. High-component and breed-based premiums.

If you’ve got Jerseys, Guernseys, or a crossbred herd punching high components, there may be more value in that milk than your current contract recognises. Work commissioned by Jersey Australia has shown that high-density milk is around 8.5 cents per kg of milk solids cheaper for processors to cart and handle than standard Holstein milk. In practice, that cost advantage doesn’t always flow back to the farm, but it’s there. In the UK retail space, Tesco’s Finest Jersey Whole Milk sits at about £1.90 per litre, significantly above standard whole milk pricing. And internationally, branded A2 or Guernsey milk lines have been shown to command premiums of 15–25% over organic milk. If you’ve already got the genetics—or you’re considering shifting your sire strategy—component-focused or breed-based differentiation can be part of a repositioning play.

3. Sustainability income streams.

There’s also money—modest, but real—attached to sustainability. The UK Dairy Carbon Network project, launched in 2025, is working with dozens of dairy farms across the main dairy regions to pilot carbon-reduction and data-collection initiatives. On the buyer side, Sainsbury’s revised its cost-of-production model and allocated about £1.7m in additional payments for dairy farmers in its Sainsbury’s Dairy Development Group, specifically linked to sustainability improvements and feed sourcing. Arla’s points-based Sustainability Incentive has rewarded farmer-owners for actions such as reducing emissions, improving slurry management, and enhancing biodiversity. None of these schemes save a broken model, but they can add a few ppl to the cheque for farms already leaning into lower-carbon, data-backed practices.

4. Organic conversion.

AHDB’s Q2 2025 dairy review pointed out that GB organic milk deliveries grew by 12.6% in that quarter, and noted tight organic supplies elsewhere in Europe. At the same time, demand for organic dairy in the UK grocery sector has remained relatively firm. For lower-input systems already close to organic standards, the shift can bring a premium robust enough to change the overall margin picture, though the conversion period and certification costs need careful modelling and lender discussion.

| Repositioning Path | Typical Volume Uplift | Margin Improvement (ppl) | Implementation Cost | Setup Time / Payback | Key Barriers | Fit for 150–350 Herd? |

| On-Farm Milk Vending (5–10% of production) | 5–10% of herd volume | +40–50 ppl(on vended litres) | £15k–£30k (machine, setup, compliance) | 3–6 months setup; 12–18 months ROI | Footfall dependent; food safety & licensing; labour for operation | Good (near urban/tourist routes) |

| High-Component / Breed Premium (Jersey, Guernsey, A2) | 0% (same milk, recontracted) | +3–8 ppl(premium vs. commodity) | Genetic investment only (sire costs, 2–3 generation lag) | 2–3 years (herd genetics shift) | Requires genetic strategy & buyer confidence; niche market risk | Strong(established bloodlines only) |

| Sustainability Payments (Carbon Network, Sainsbury’s DSG, Arla Scheme) | 0% (same production) | +0.5–2 ppl(modest but easy) | None (audit/data collation only) | Immediate (baseline audit) | Admin burden; baseline must be established; limited scheme growth | Moderate(entry-level option) |

| Organic Conversion | 0% (typically –5% during transition) | +8–12 ppl(certified organic premium) | £5k–£15k (certification, system audit) | 18–24 months certification; payback 2–3 years | Long transition; tight grass/forage margin; conversion costs; market saturation risk | Moderate–Strong(low-input systems only) |

None of these paths is a silver bullet. Each demands specific conditions, capital, time, or skill sets. But it’s worth putting them on the table before deciding your only options are to try to become Group A overnight—or plan a dignified exit. For some Group B herds, the real play is to change how value is captured, not just to crank out more bulk litres.

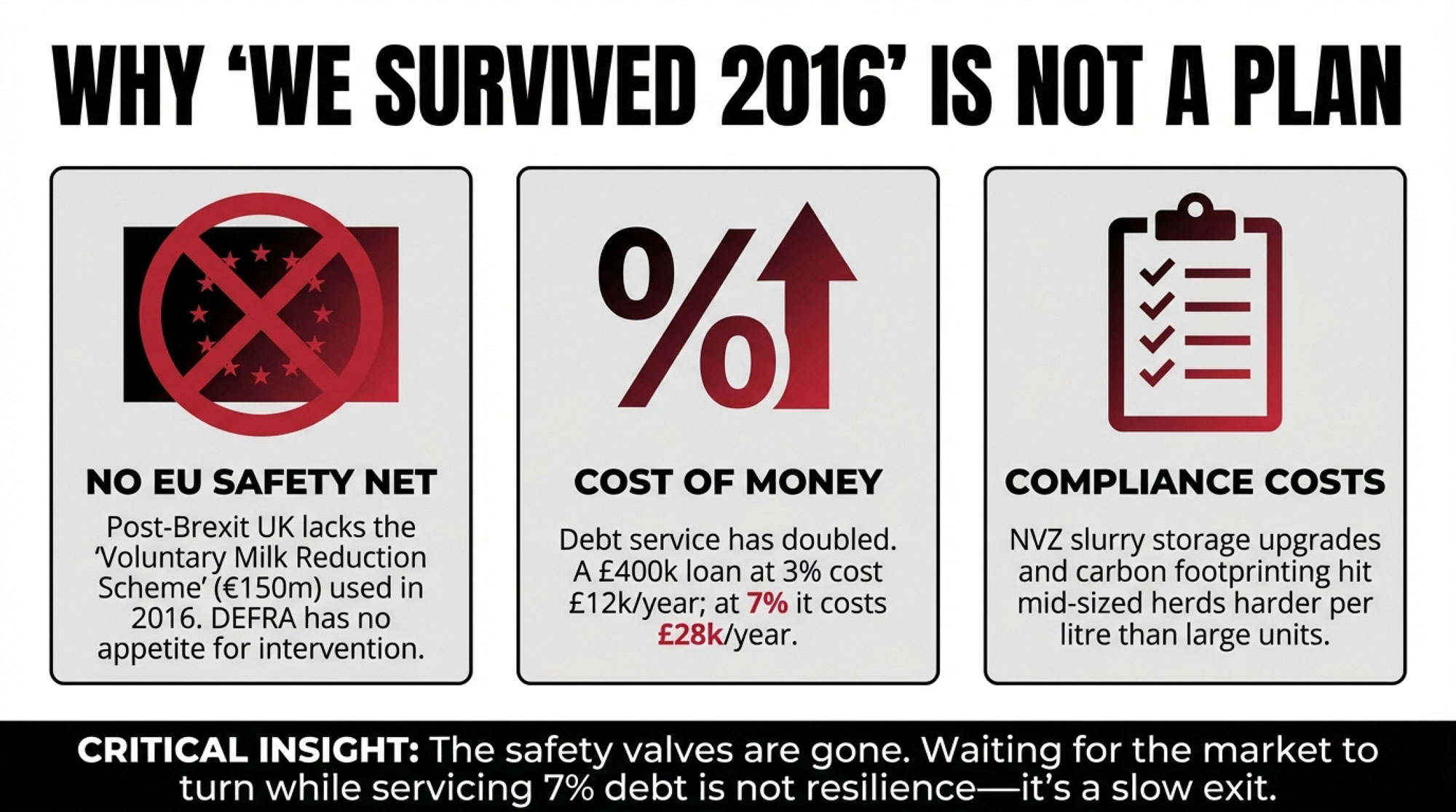

Why “We Got Through 2009 and 2016” Isn’t a Plan Anymore

You hear it all the time, and I get why: “We survived 2009. We survived 2016. We’ll ride this one out, too.”

Those scars matter. But some of the pieces on the board have changed.

There’s no EU-style relief valve sitting in the background

During the 2015–2016 crisis, the European Commission introduced a Voluntary Milk Reduction Scheme worth €150 million, paying farmers 14 euro cents per kilogram of reduced milk. The scheme, set out in Regulation 2016/1612 and later analysed by the European Court of Auditors, aimed to cut deliveries to dairies by around 1.1 million tonnes. In addition, Article 222 of the CMO was temporarily activated to enable coordinated production planning.

Post‑Brexit UK does not have that machinery in place:

- AHDB can analyse and warn, but it doesn’t have a budget or mandate to pay for volume reduction.

- DEFRA has shown no appetite for direct dairy market intervention of that sort.

- The specific legal tools Brussels used in 2016 don’t have a simple UK equivalent.

So waiting for an EU-style scheme to take the pressure off isn’t realistic.

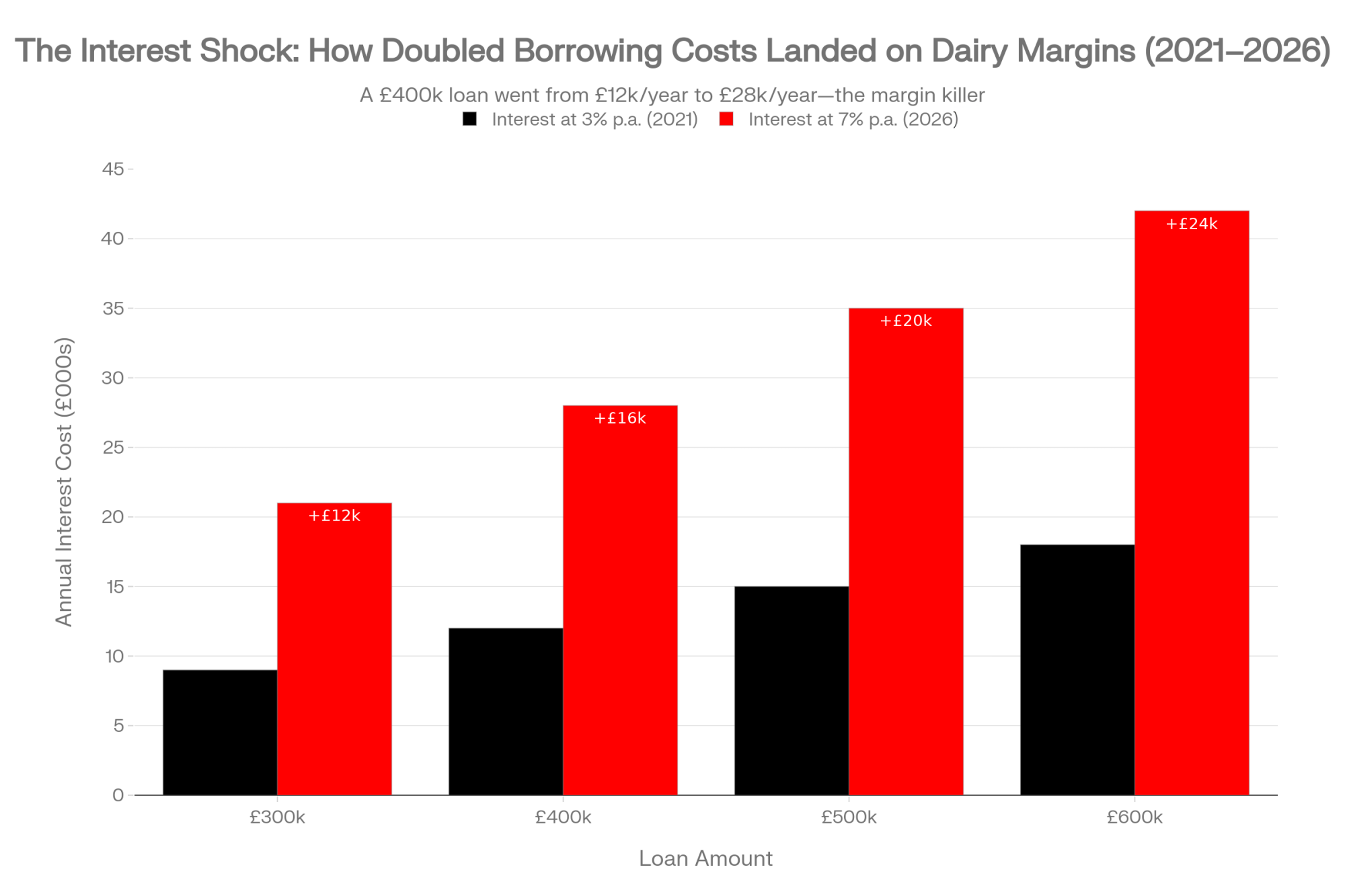

The cost of money has doubled—or worse

A lot of herds invested heavily between 2021 and 2023: robots, parlour rebuilds, cubicle extensions, and new slurry systems. The logic made sense when borrowing was cheap.

Fast forward a few years:

- A £400,000 loan at 3% costs about £12,000 a year in interest.

- The same loan at 7% costs around £28,000 a year.

- Double that borrowing, and you’re looking at a £30–£60k annual interest bill just to stand still.

| Loan Amount | Interest at 3% p.a. | Interest at 7% p.a. | Annual Swing |

|---|---|---|---|

| £300,000 | £9,000 | £21,000 | +£12,000 |

| £400,000 | £12,000 | £28,000 | +£16,000 |

| £500,000 | £15,000 | £35,000 | +£20,000 |

| £600,000 | £18,000 | £42,000 | +£24,000 |

When your milk price drops but your interest bill doesn’t, the margin squeeze lands faster and harder than in 2009 or 2016.

Compliance and sustainability costs bite differently

On top of price and finance, you’ve got the slow grind of:

- Slurry storage and handling upgrades in NVZs and other sensitive areas.

- Carbon footprinting and greenhouse gas metrics are increasingly tied to contract terms, premiums, or access to certain pools.

- Stricter expectations around lameness, SCC, mastitis control, calf care, and housing.

Bigger units can spread these costs over more litres. Mid-sized herds feel a much bigger hit per litre.

One looming fear—inheritance tax changes—has at least been softened. GOV.UK guidance from December 2025 confirms that 100% Agricultural Property Relief will apply to up to £2.5m per individual or £5m per couple, rather than the initially floated £1m cap. That still matters for higher‑value land and diversified businesses, but it’s no longer an automatic death sentence for the typical 250–300 cow family farm.

Right now, for most GB herds, the main squeeze isn’t tax. It’s day‑to‑day margin—and whether your business model matches the structure processors are actively building.

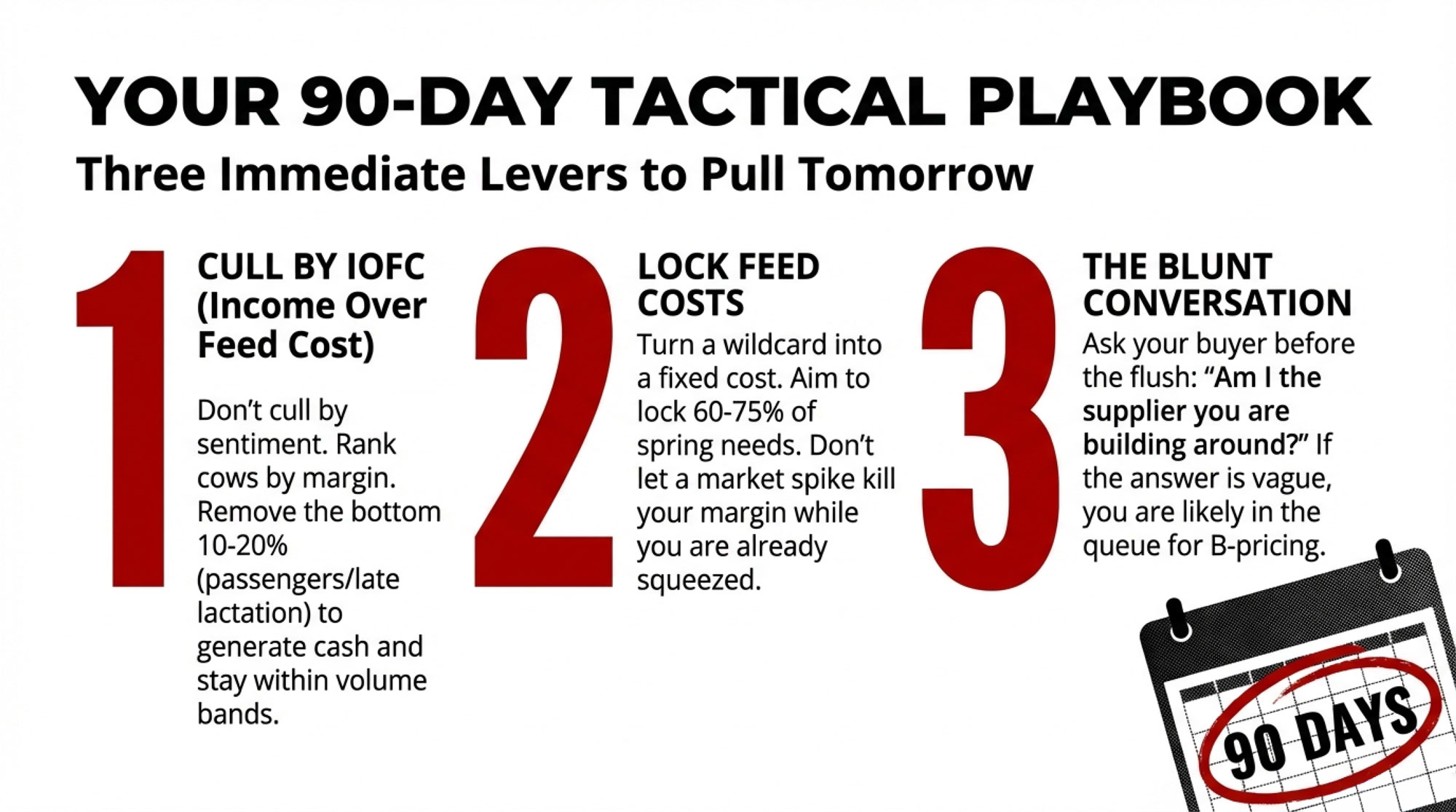

The Next 90 Days: Three Levers That Actually Move the Needle

If your gut feeling is, “I’m not ready to sell; I still want this place in the game,” then the next 90 days aren’t just another quarter. They’re your window to buy time and choice.

Here are three levers that actually move numbers on real farms.

1. Cull for cash flow and contract fit—not nostalgia

Cull cow values have been relatively strong through 2024–2025 off the back of firm beef markets, according to AHDB deadweight price reporting. The herds using that to their advantage are:

- Ranking cows on Income Over Feed Cost (IOFC) or a similar margin metric.

- Flagging the bottom 10–20%: repeat mastitis offenders, long‑term lame, low‑yield late lactation, chronic fertility passengers.

- Laying that list against their spring flush forecast and contract band.

If your realistic projection shows you 10–15% over your band in April–June, ask yourself:

- Are those litres likely to be fully paid, B‑priced, or effectively penalised?

- Would moving that bottom 10–15% now:

- Bring you back inside your volume ceiling?

- Cut feed, bedding, and labour going into turnout?

- Put a meaningful cash lump into the business at a time you can really use it?

You’re not “giving up” by doing this. You’re choosing to fight with a right‑sized, higher‑margin herd instead of maxing litres and getting hammered on the last ones out of the parlour.

2. Turn feed from a wildcard into a known number

Honestly, this is where plenty of mid-sized herds get caught out. Larger outfits often have someone watching grain markets, dealing on forward contracts, and working closely with nutritionists. Many 180–320 cow herds still buy feed on a “call when the bin’s low” basis.

With milk-to-feed looking attractive, a sudden jump in purchased feed could be one of the few punches that still floors you.

A practical way to de-risk it:

- Estimate your March–September purchased feed spend. On a 250‑cow herd, £40,000–£60,000 isn’t unusual.

- Sit down with your nutritionist or feed rep and explore locking in 60–75% of that volume at current prices.

- Run three basic scenarios on paper:

- Feed stays flat.

- Feed rises 15%.

- Feed rises 30% (weather, war, or logistics go sideways).

Then ask, “In the ugly scenario, do we still keep the bank and our key suppliers happy?” If the honest answer is “no” or “only just,” then taking a big chunk of that risk off the table starts to look less like gambling and more like common sense.

Locking isn’t about trying to outsmart the market. It’s about making sure a feed spike doesn’t land on top of everything else while you’re already juggling cash flow and contract limits.

3. Have the blunt volume talk with your buyer before the flush

Processors usually start thinking about spring flush volumes and band reviews early in the year. The worst time to be phoning your field rep is late April, when the grass has exploded, and you’re already tens of thousands of litres over where they want you.

Go in prepared:

- Take your last three years of daily average litres for April–June.

- Take current cow numbers and expected calvings.

- Take the culling you’re planning from that bottom-end IOFC list.

Then say, “If we run as planned, I’m likely to be about X% over my current band in the flush.”

Three questions matter:

- “Is there any scope to lift my band if I commit to trimming the tail‑end and doing what I can to flatten the peak?”

- “If not, can you give me two to three weeks’ warning before you move to B‑pricing or stop taking extra milk so I can react on‑farm?”

- “Candidly, am I the sort of supplier you see yourselves building around over the next few years—or should I be thinking about other options?”

You might not like the answer to that third one. But if your buyer implies, “We’re effectively full, and you’re not in Tier A,” that’s incredibly valuable information when you’re deciding whether to invest, pivot into a niche, or plan a managed exit.

How to Judge Which Side You’re On

Let’s talk about the hard bit: structural fit.

Arla’s £179m mozzarella plant and Müller’s £45m Skelmersdale project aren’t charity. They’re engineered around a particular kind of supplier profile. You can’t control how that profile is defined. But you can work out how close—or far—you are from it.

Here are four questions worth putting on the table with your family, your accountant, and maybe your lender.

1. What’s my real cost-of-production?

Not feed plus vet. Full cost. That means:

- All labour, including a sensible wage for you and anyone working “for free” in the family.

- Power, parlour, and yard running costs, machinery.

- Depreciation and repairs.

- Finance costs and a realistic return on owned land and capital.

If you don’t have a precise figure, use AHDB and Kingshay benchmarking to get a sensible range for herds like yours.

As a rule of thumb:

- If your full cost-of-production is in the low‑to‑mid 30s ppl and you’re on a decent, aligned, or premium contract, you’re playing something close to the game processors are building for.

- If your full costs are pushing into the mid‑40s ppl or higher and most of your milk cheques are based on manufacturing/commodity prices in the low‑to‑mid 30s, then you’re dealing with a structural margin problem—not a “try a bit harder” problem.

Both kinds of farms can have excellent cow care, strong, fresh cow management, and top genetics. The difference is what the numbers say when every cost is on the page.

2. What kind of contract am I really hanging my future on?

Look at your current deal with cold eyes.

- Aligned, retail, or sustainability-based contracts: better base prices, clearer bonus structures, often some protection from the worst of global powder swings.

- Manufacturing or commodity contracts with spot exposure: more volatile, more exposed to global prices, less room to negotiate in a downturn.

Then ask:

- “Is there a realistic path for us to move up the contract ladder in the next 2–3 years?”

- “If not, do I really want to tie big capital bets—robots, new sheds, more cows—to this style of contract?”

You can succeed on a manufacturing contract—but the bar for cost-of-production and resilience is much higher.

3. If nothing major changes, what does 2030 look like on this farm?

This one can be uncomfortable, but it’s critical.

Picture it:

- Same basic cow numbers.

- Similar contract type.

- Environmental and slurry rules are a notch tighter—because every signal says they will be.

- Labour is still hard to find and keep.

Does that picture energise you? Or exhausted just thinking about it?

If you don’t like what you see, then 2026 shouldn’t just be about “surviving this slump.” It should be about using this slump as a pivot point—toward a model that fits the new structure, a differentiated niche, or an exit that preserves as much value and choice as possible.

4. Am I fighting to reposition—or just fighting not to stop?

There’s a huge difference between:

- Fighting to reposition: tightening the herd with IOFC-based culling, altering your system, pushing for a better contract tier, exploring niches like on‑farm vending, component‑driven milk, sustainability income, or organic.

- Fighting simply to not be the one who quits, even when the numbers show the current structure is slowly grinding you down.

Both fights are exhausting. Only one change changes the trajectory.

Processors, lenders, and markets don’t distinguish between “noble effort” and “strategic adaptation.” They respond to cost, reliability, and fit. So it’s worth being brutally honest with yourself about which fight you’re really in.

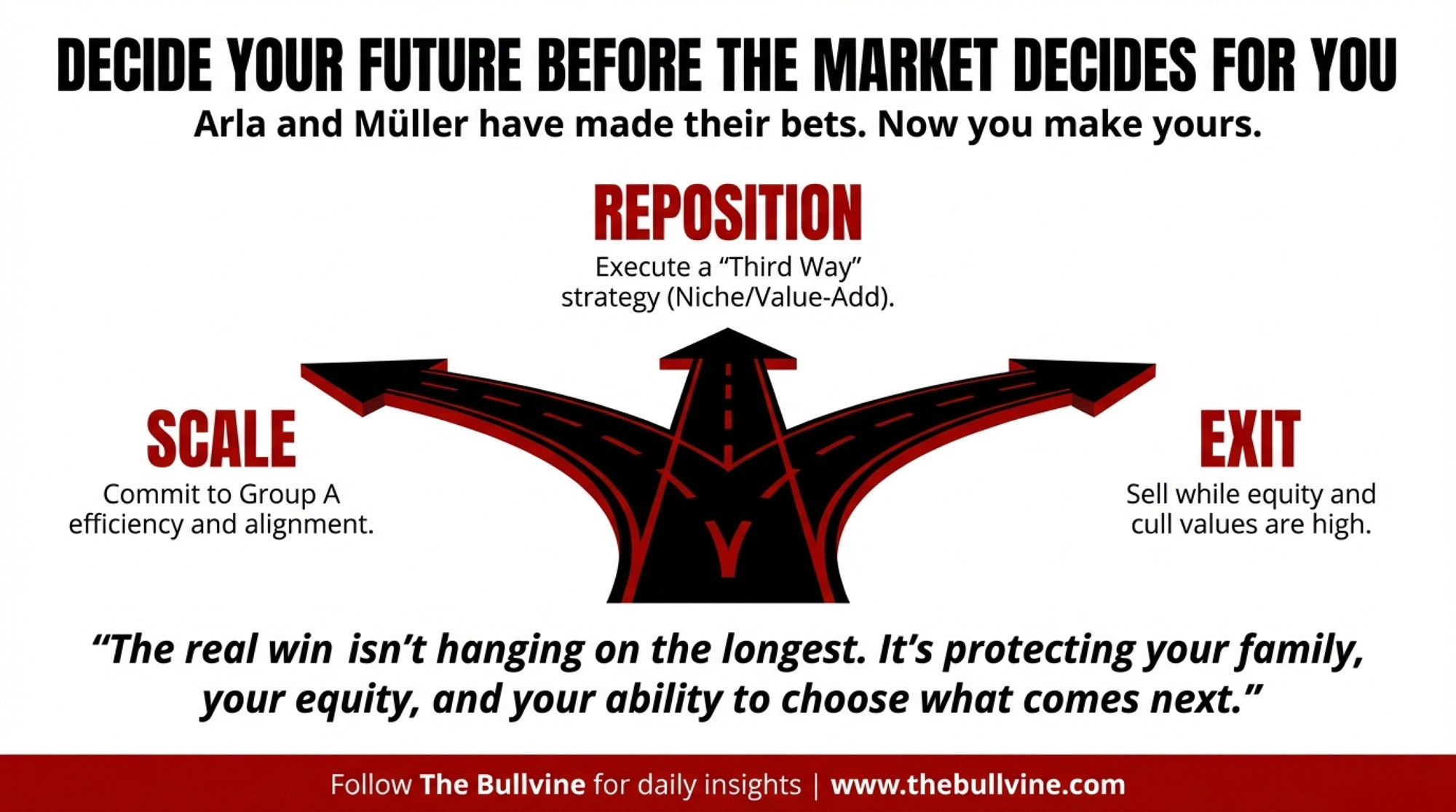

The Bottom Line

Let’s pull this back to something you can actually act on.

1. Know which game you’re in.

If your true full cost-of-production is in the low‑30s and you’re on an aligned or premium contract, you’re in the positioning and growth game. If your full costs are in the mid‑40s and you’re selling mostly commodity milk, you’re in the survival or transition game—unless you’re actively building one of those “third way” niches that changes how your litres are valued.

The same move—like keeping every cow to push litres—means completely different things in those two games.

| Herd Size | Full CoP (ppl) | Typical Milk Price (ppl) | Margin per Litre (ppl) |

| 120 | 46 | 32 | –14 (loss) |

| 180 | 44 | 32 | –12 (loss) |

| 220 | 42 | 32 | –10 (loss) |

| 280 | 40 | 32 | –8 (loss) |

| 350 | 38 | 32 | –6 (marginal) |

| 400 | 35 | 38 (aligned) | +3 (small profit) |

| 500 | 32 | 40 (retail premium) | +8 (profit) |

| 600 | 30 | 42 (aligned/branded) | +12 (profit) |

2. Use the next 90 days to buy time and clarity—not to delay reality.

Strategic culling while cull values are still reasonably strong, locking a meaningful slice of your feed costs, and having a tough but honest conversation with your buyer about bands and long‑term fit won’t magically fix a broken model. But those moves can buy you 6–12 months where you’re not permanently fire‑fighting, and that’s when good decisions get made.

3. Stop treating structural pain as a personal failure.

If your numbers don’t stack, it’s not because you’ve suddenly become bad at dairying. Plenty of 180–300 cow herds with good genetics, tidy parlours, and solid fresh cow management are getting squeezed because the rules have changed—not because they forgot how to farm. Seeing that clearly is the first step to deciding whether to scale, reposition, or step out on your own terms.

4. Think 2030 first, then decide your 2026 moves.

Don’t just ask, “How do I get through this year?” Ask, “What do I want my life, my family, and this business to look like in four or five years?” Then decide whether you’re:

- Fighting to scale into Group A,

- Fighting to carve out a differentiated, better‑paid niche as a mid‑sized producer, or

- Fighting to exit with your equity and dignity intact instead of letting events decide for you.

Arla’s £179m mozzarella project at Taw Valley and Müller’s £45m powder investment at Skelmersdale are not signs that UK dairy is dying. They’re signs that UK dairy is being sorted into:

- The farms that those plants will depend on,

- The farms that find a different way to capture value, and

- The farms they expect to replace.

You can’t rewrite their investment plan. But you absolutely can decide whether your next steps make it more likely that you’re in the group they’re betting on, in a niche they can’t easily commoditise, or in the camp that cashes out on its own terms rather than getting pushed.

Either way, the real win isn’t “hanging on the longest.” It’s protecting your family, protecting your equity, and protecting your ability to choose what comes next.

And if you’re wrestling with those questions on your own farm right now, you’re not alone. The more honestly we talk about it, the better the decisions we’ll all make.

Key Takeaways

- The paradox is real: UK milk is up 6.8% to record levels, and processors are investing £368m+, yet mid-sized herds feel more fragile—because that money isn’t being bet on every farm.

- Cheap feed is a trap: A 20-year-high milk-to-feed ratio looks like an opportunity, but once labour, power, and doubled interest costs are in, many 150–350 cow herds on commodity contracts lose money on every extra litre.

- Processors are sorting suppliers—not saving them: Arla’s £179m Taw Valley mozzarella plant and Müller’s £45m Skelmersdale upgrade are built around scale-efficient, aligned herds. Mid-sized, manufacturing-exposed farms are on the wrong side of that bet.

- The next 90 days matter: Cull the bottom 10–20% by IOFC, lock 60–75% of spring feed costs now, and have a blunt conversation with your buyer about volume bands and long-term fit before the flush hits.

- There’s a third way beyond scale or exit: Direct-to-consumer vending (£1/litre vs 22p), high-component breed premiums, sustainability bonuses, and organic conversion offer realistic repositioning paths for mid-sized herds.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Four Numbers Every Dairy Producer Needs to Calculate This Week – This surgical framework arms you with the precise math needed to determine your liquidity runway and competitive investment ratio. It reveals exactly whether you should double down on automation or execute a strategic exit while you still control the equity.

- More Milk, Fewer Farms, $250K at Risk: The 2026 Numbers Every Dairy Needs to Run – This deep-dive exposes the brutal $250,000 margin gap facing 500-cow herds as they navigate the 2026 market reset. It delivers the strategy required to position your operation within regional supply networks before the next wave of consolidation hits.

- August USDA Milk Production Report Breakdown: Why 19.52 Billion Pounds of Richer Milk Changes the Game – This analysis breaks down how a permanent genetic revolution is decoupling milk volume from component value. It reveals the advantage of shifting from bulk production to high-component specialization to survive a market where supply management is no longer optional.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!