Your 72-Hour Playbook—Generators, Fuel, Water, and the MLP Paperwork That Actually Pays Back

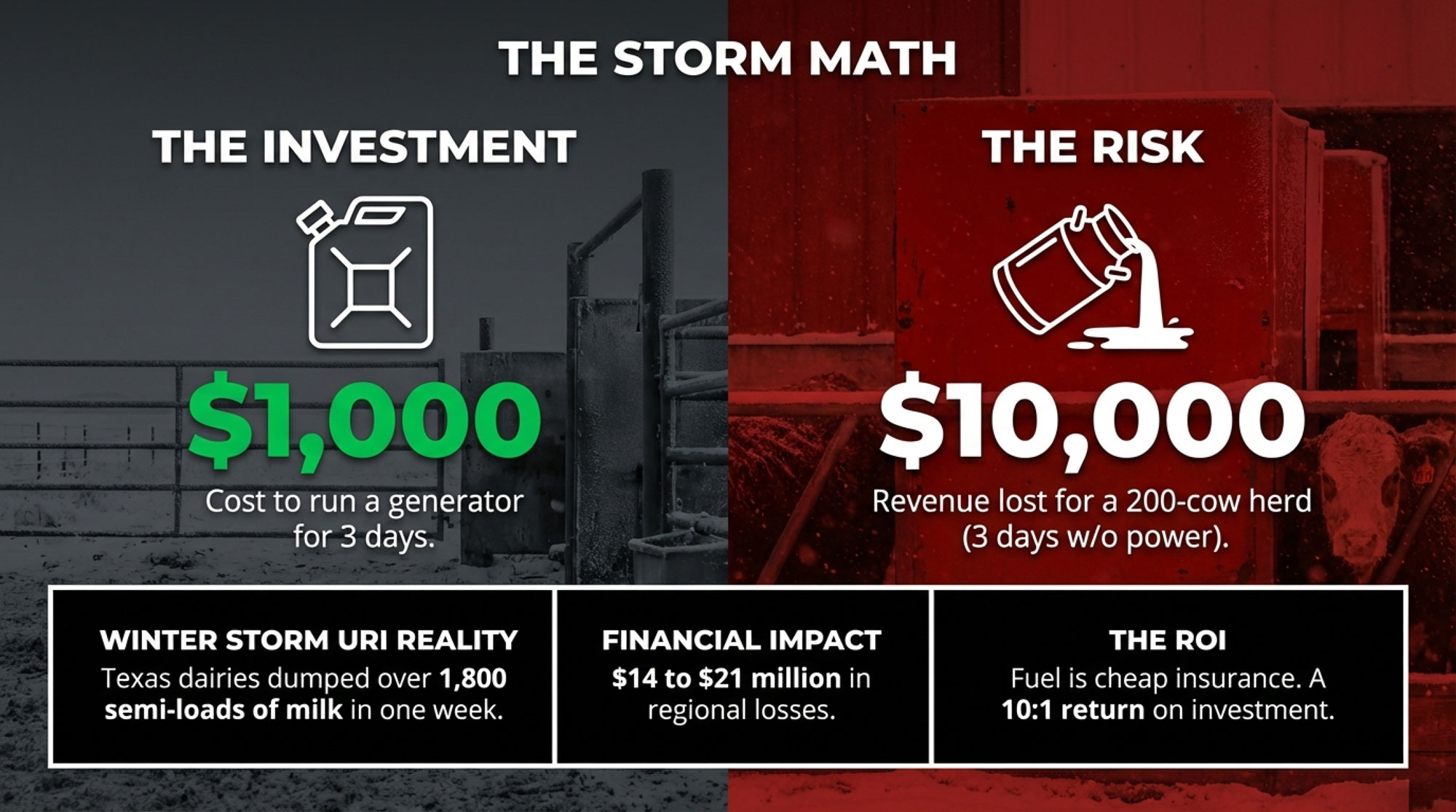

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Winter Storm Uri saw Texas dairies dump over 1,800 semi-loads of milk, resulting in $14 to $21 million in losses in a single week. For a 200-cow herd, three days without power means roughly $10,000 in dumped milk before equipment failures or dead animals add to the toll. The math is simple: $1,000 in diesel keeps your generator running; skipping it risks ten times that down the drain. This playbook covers the 72 hours before a major storm hits—generator sizing, fuel planning, water backup, cold-stress feeding, staffing decisions, and the H5N1 biosecurity realities now complicating neighbor-to-neighbor mutual aid. It also details the USDA Milk Loss Program paperwork (dates, volumes, written reasons) that can recover 75-90% of your losses—but only if records exist before the bulk tank overflows. From 70-cow Ontario tie-stalls to 2,000-cow Texas dry lots, the dairies that survive these storms aren’t lucky—they’re the ones who ran the numbers while the sky was still clear.

So here’s a question I’ve been asking farmers lately, and you know, most don’t have a great answer: how many days can your operation actually run if the grid goes down and stays down?

I bring this up because big winter storms aren’t rare “acts of God” anymore. They’re stress tests—of your barns, your people, and honestly, your balance sheet. When Winter Storm Uri slammed Texas in February 2021, agricultural economists with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension estimated initial losses at more than $600 million. And here’s what stuck with me: AgriLife Extension director Jeff Hyde, Ph.D., warned those costs could “plague many producers for years to come.” That wasn’t just a bad week. That was a structural blow to many good operations.

Let me bring that down to a scale we can actually picture. Say you’re milking 200 cows, averaging around 80 lb per cow per day. That’s 16,000 lb daily, or about 160 cwt. At 20 dollars per cwt—your number might be higher or lower depending on components and premiums—one day of completely dumped milk means roughly 3,200 dollars in gross revenue gone. Three days? You’re staring at nearly 10,000 dollars, and that’s before we even talk about butterfat levels or quality premiums you’re losing.

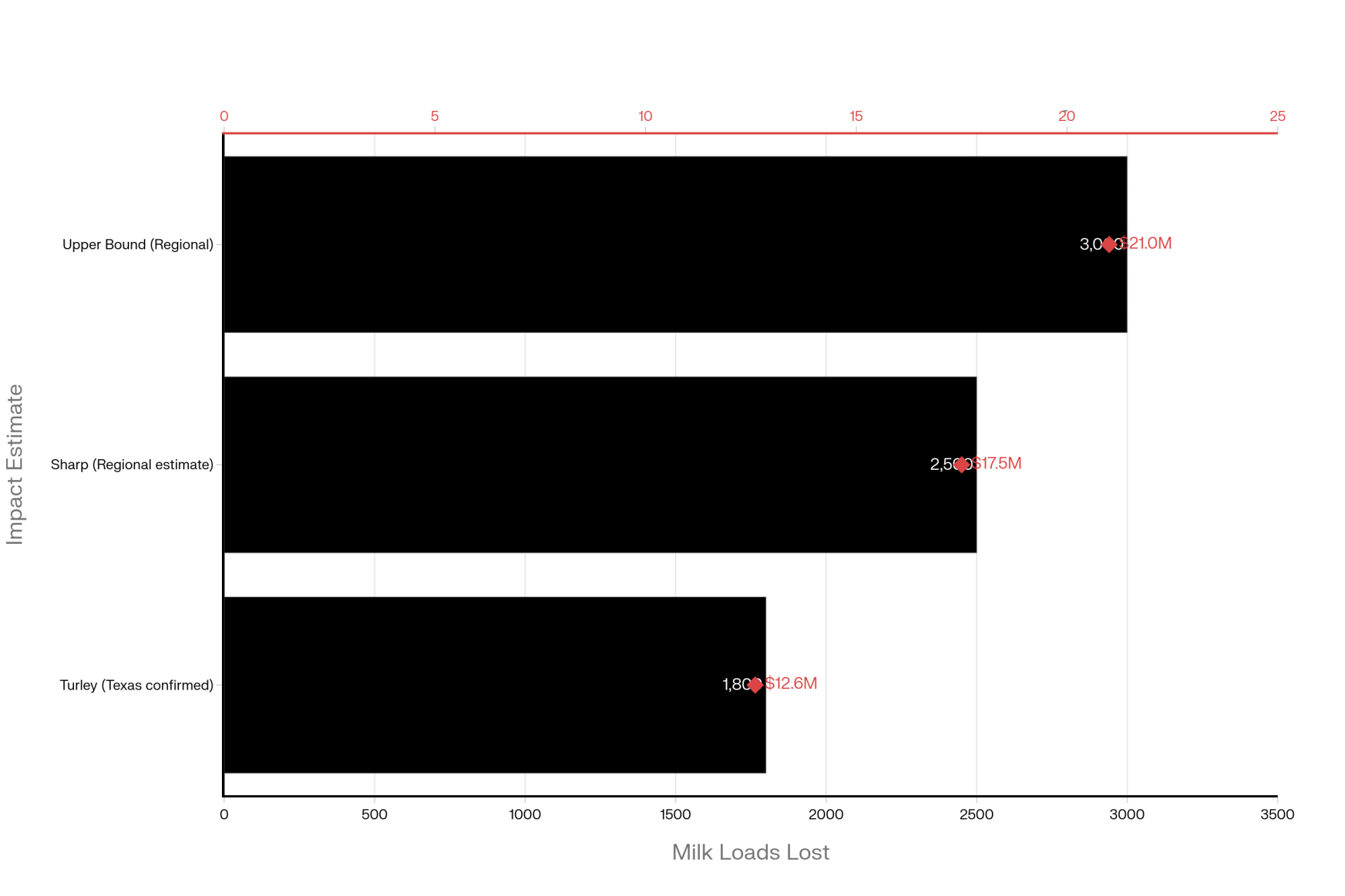

During Uri, Darren Turley—he’s the executive director of the Texas Association of Dairymen—told Brownfield Ag News that Texas dairies ended up dumping over 1,800 semi loads of milk in roughly a week. Plants couldn’t process it, trucks couldn’t move, and power and natural gas were just gone. Dairy market analyst Sarina Sharp, estimated the regional total at 2,000 to 3,000 loads. If you put even a conservative value of 7,000 dollars per load on that, we’re talking 14 to 21 million dollars of milk literally washed down the drain.

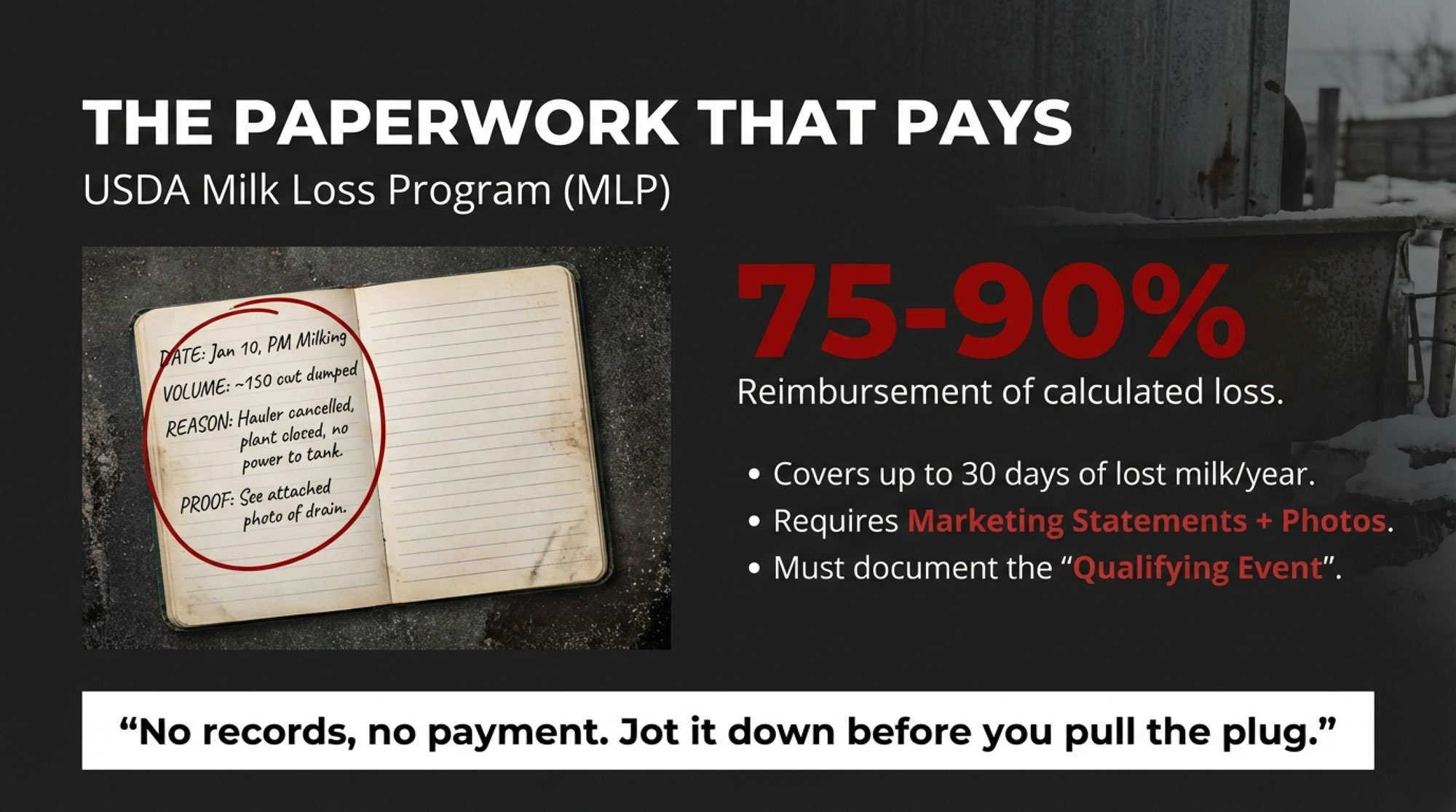

Here’s what’s encouraging, though: policy actually reacted. In 2023, USDA’s Farm Service Agency rolled out the Milk Loss Program—MLP for short—to compensate dairy operations for milk that got dumped or removed from commercial markets due to qualifying natural disasters. The program covers events from 2020, 2021, and 2022, and the rules are pretty specific: eligible dairies can claim up to 30 days of lost milk per year, with payments at 90 percent of the calculated loss for underserved producers and 75 percent for everyone else.

So looking ahead to the next named winter storm, the real question becomes: in the 72 hours before it hits, what can you do on your dairy—right here, with your labor, cash flow, and setup—to keep the next storm from erasing months of hard-won margin?

Key Numbers Worth Keeping in Your Head

Before we get into the details, here are the figures I’d jot on a notepad:

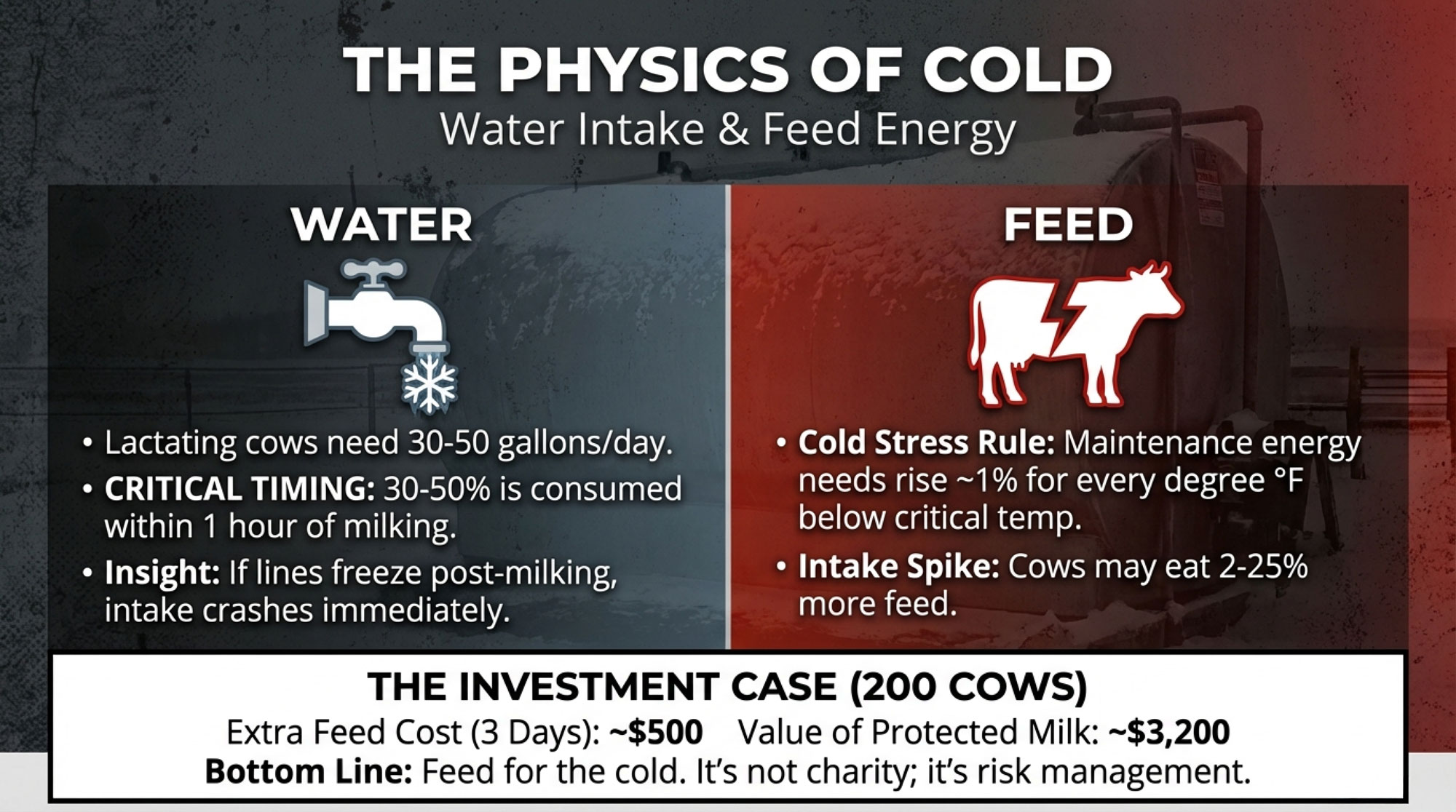

- 30–50 gallons/cow/day — typical water intake for lactating cows, according to Penn State Extension

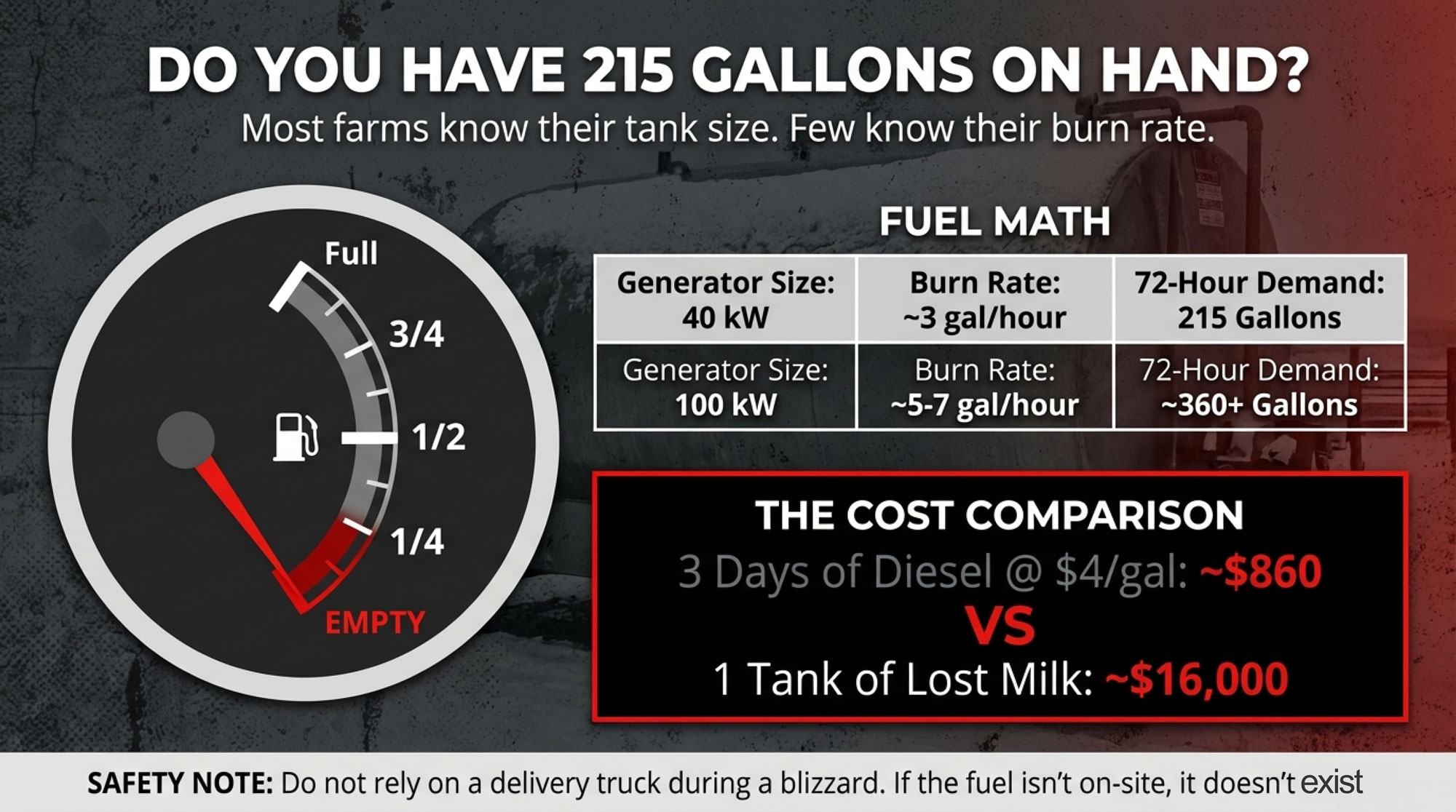

- 2–4 gal/hour — approximate fuel burn for a 40 kW diesel generator, depending on load, per industry fuel consumption data

- 5–7 gal/hour — fuel consumption range for larger 100 kW units at working capacity

- About 1% per °F — added maintenance energy demand once cattle drop below their lower critical temperature, per SDSU and NDSU Extension

- 2–25% — range of intake increases you might see in cold-stressed cattle when forage quality allows, again from SDSU

- 30 days — maximum MLP coverage per year

- 75% / 90% — MLP payment rates for standard producers versus underserved producers

- $3.6 billion — estimated uncovered U.S. farm losses from 2020 natural disasters alone, according to American Farm Bureau Federation analysis

- $21+ billion — crop and rangeland losses from 2022 severe weather events, per AFBF

A 10-Minute “If You Don’t Do Anything Else” Checklist

You know, what I’ve found talking to producers is that you don’t need a thick binder to be materially more ready. You need a few focused moves. If you only have ten minutes this week, I’d put them here.

- Run the generator under real load.

Start it, switch through the transfer switch, and put actual critical loads on it: vacuum pump, milk pump, cooling, one well pump, and key lights. Let it run 30–60 minutes. The true test—and every farm electrical guide will tell you this—is whether it can start and carry those motors without sagging or tripping. Running smooth with no load? That tells you almost nothing. - Know your fuel math, not just your tank size.

Industry fuel consumption charts show that a 40-kilowatt diesel generator under decent load burns about 2–4 gallons of fuel per hour, while a 100-kilowatt unit typically requires 5–7 gallons an hour at working capacity. Run that 40 kW set at around 3 gal/hour for 72 hours straight, and you’re at roughly 215 gallons. At 4 dollars per gallon, that’s about 860 dollars of diesel. Now put that against one 25,000-liter load of dumped milk—around 700–800 cwt—at 20 dollars per cwt. That’s 14,000 to 16,000 dollars gone. Three days of fuel starts looking like pretty cheap insurance. - Stage three to five days of water access.

Penn State Extension notes that lactating dairy cows typically drink 30–50 gallons of water per day, with most of that from drinking rather than from feed moisture. Use 35–40 gallons as a planning number, and that same 200-cow herd needs 7,000–8,000 gallons a day. Over three days, you’re north of 20,000 gallons. Nurse tanks, overhead storage, and extra troughs positioned now give you a buffer if lines freeze or a pump fails. - Walk every water line and heated waterer.

In colder regions—and this is consistently shown in livestock water system bulletins from Ontario and the northern U.S. states—self-regulating heat cable rated for potable water is recommended for exposed or problem lines. It adjusts its output based on temperature and is considered safer than constant-wattage tape. Flip breakers, feel heaters, check thermostats, and look hard at elbows, risers, and any line you’ve “meant to insulate later.” - Look at rations through a cold-stress lens.

SDSU Extension and NDSU both use a practical rule of thumb: once cattle are below their lower critical temperature, maintenance energy requirements rise by about 1% for every degree Fahrenheit below that point. They also report that cattle under cold stress often increase intake by 2 to 25 percent when forage quality allows, with the higher end of that range kicking in when effective temperatures drop below about 5°F. So if cows are effectively 18°F below LCT, you could be looking at around 18 percent more energy demand. On a 200-cow herd feeding 50 lb/head/day, that’s an extra 9 lb/head/day—1,800 lb of TMR daily. At 8 cents per lb of dry matter, that’s roughly 144 dollars per day. Over three days, call it 400–500 dollars in extra feed. Put that against the risk of losing 3–4 lb of milk per cow per day over three days—2,400–3,200 dollars at 20 dollars per cwt—and the math very clearly favors feeding for the cold. - Get brutally honest about who can actually reach the farm.

Farm emergency planning tools in British Columbia and the Prairie provinces encourage mapping where employees live and how storms affect their routes. More dairies now designate one or two core people—often the owner and a key herdsman or herdswoman—as “on-farm no matter what,” and set clear thresholds beyond which staff farther away are told not to risk the roads. That clarity saves accidents and, indirectly, protects the herd. - Talk to your milk hauler and your co-op or processor.

Brownfield’s coverage of Uri showed how chaotic those first days were for plants, haulers, and farms. Many processors in Texas, the Upper Midwest, and the Northeast now have more defined storm protocols. This is the time to ask, “If the plant is down or roads are closed for two days, what happens to my milk?” Their answer will tell you whether your real risk is a full tank or a dead tank. - Post an emergency contact sheet where everyone can see it.

Vet clinic, hauler dispatch, field rep, electric and gas utilities, fuel supplier, FSA office, insurance agent, and a couple of neighbors—that’s the bare-bones list most farm emergency guides recommend. Tape it in the milk house. When phones die or get lost, that paper is still there. - Add bedding and wind protection for outside groups.

Cold-stress articles from NDSU, Wisconsin, and others note that effective windbreaks and deep, dry bedding can substantially reduce energy requirements and help cattle maintain condition during severe cold. Straw, stalks, bale stacks, and panel lines are low-tech, high-ROI tools to stage before the weather hits. - Turn documentation into a habit, not a scramble.

The MLP fact sheet emphasizes that producers must document dates and volumes of dumped or removed milk, provide marketing statements, and describe the qualifying event and how it prevented normal marketing. Similar documentation underpins the Livestock Indemnity Program, ELAP, and the Emergency Conservation Program. Jotting a quick note—”PM milking, Jan 10, ~150 cwt dumped, hauler cancelled, plant closed”—and snapping a photo can be worth thousands later.

If that’s all you manage before the next big system, you’re still a long way ahead of where many good dairies found themselves going into Uri or the big High Plains and Dakota blizzards.

72–48 Hours Out: Getting Real About Power and Water

Looking at post-storm reports across Texas, the High Plains, and eastern Canada, the pattern is pretty consistent: herds with even basic backup power and water plans had miserable days, but they stayed in the game. Herds with no plan? They jumped straight to crisis.

Sizing Backup Power for the Farm You Actually Run

In many Ontario tie-stalls and Wisconsin freestalls, as well as smaller parlors in New York and Vermont, backup power usually means a PTO generator or an older diesel tied into the parlor and one well. In larger dry lot systems in New Mexico or the Texas Panhandle, you’ll more often see big automatic units, but you know, many 500–1,000 cow herds still depend on PTO sets.

Generator sizing guides from provincial ministries and suppliers generally start the same way:

- List your “must-run” loads: vacuum pump, milk pump, plate cooler or bulk tank compressor, at least one deep-well pump, and minimum lighting.

- Convert motor horsepower and amps to kilowatts and total your running load.

In their worked examples, modest parlor setups often fall in the 25–40 kW range for true critical loads. Once you add larger parlors, multiple compressors, robot systems, sand separation, and more ventilation, those examples quickly move into the 75–150 kW band or higher, depending on what’s bolted to the floor.

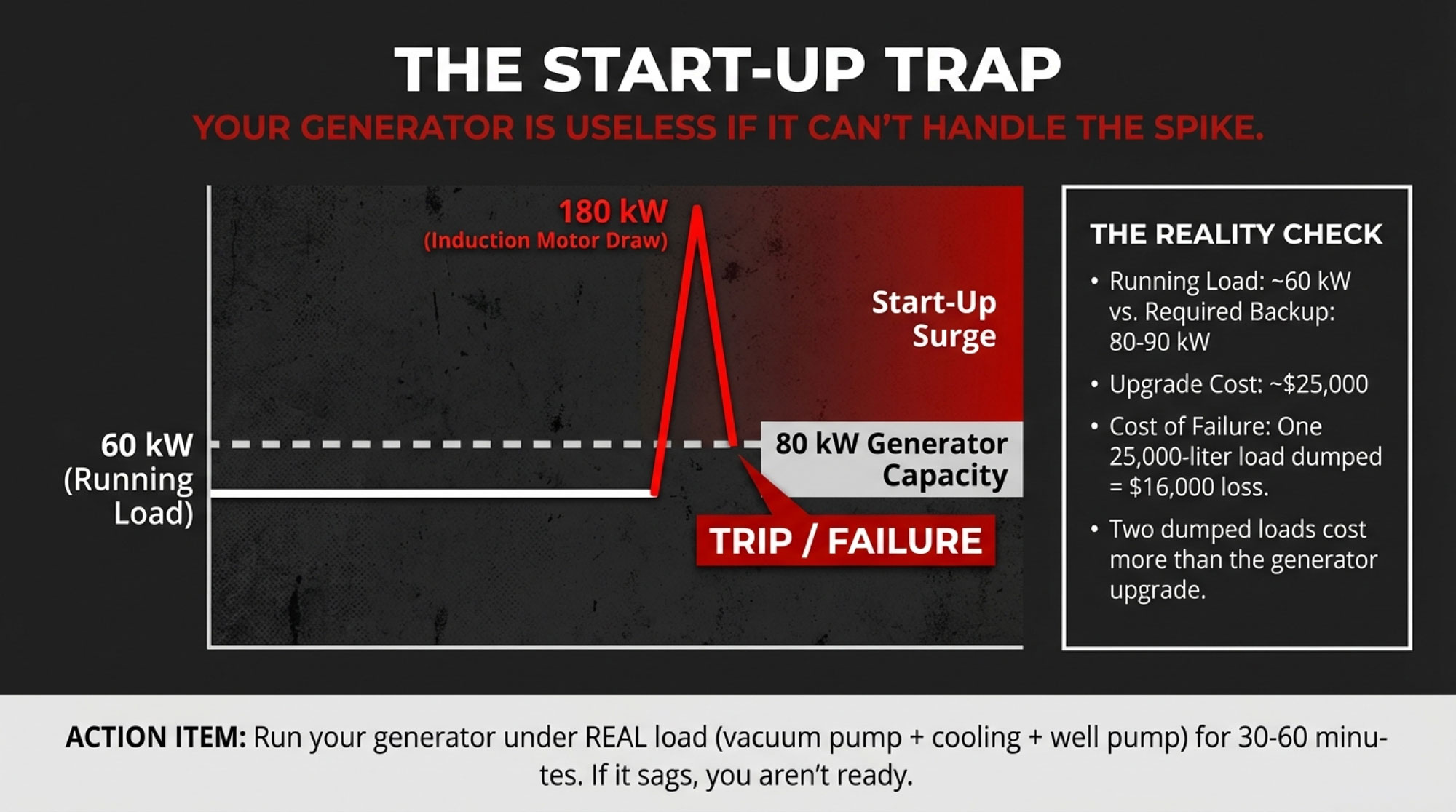

And here’s the catch that bites a lot of people: motors don’t draw their running amps when they start. Electrical references and generator manuals consistently note that induction motors can draw 2 to 3 times their running current at start-up. That’s why most electricians and sizing tools push you to build serious headroom above that neat running-load number.

So if you and your electrician calculate a critical running load of about 60 kW, it’s common to recommend a generator in the 80–90 kW range to handle multiple motors starting without constant tripping. One pattern I keep seeing: when producers balk at the bigger unit, it’s usually because they’re thinking about “amps right now,” not “worst-case start-up” during a blizzard.

| Tier & Critical Load | Est. kW Running | Recommended Gen Size | Typical Cost | Fuel/72hr @ $4/gal | What’s Covered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1: Parlor + Well + Cooling | 25–40 kW | 40–50 kW | $12,000–$18,000 | $860–$1,440 | Milking, water, bulk tank cooling |

| Tier 1+2: + Lighting + Manure | 45–65 kW | 75–90 kW | $20,000–$32,000 | $1,440–$2,160 | + Alley lights, pump-out capability |

| Full Farm (Rare) | 80–120+ kW | 120–150+ kW | $35,000–$60,000+ | $2,160–$3,600+ | Everything except non-essential loads |

| Undersized (60 kW / no headroom) | 60 kW listed | Often fails under real load | $15,000–$22,000 | $1,080/72hr | Risk: motors trip/stall at startup |

| PTO Gen (Tractor-Driven) | Variable (20–40 kW typical) | Depends on tractor | $8,000–$15,000 | Fuel from tractor tank | Limited to parlor + one well; no automatic failover |

Put some dollars on this. Say upgrading from a marginal 60 kW unit to a properly sized 90 kW backup costs around 25,000 dollars. One full 25,000- to 30,000-liter load of dumped milk, at 20 dollars per cwt, is roughly 14,000–16,000 dollars. Two loads in a week and you’ve essentially burned the cost of that larger unit—without actually owning it.

One non-negotiable point: safety. Every electrical safety sheet from utilities and farm safety programs says the same thing—use a proper transfer switch that isolates your system from the grid when the generator runs. Backfeeding through improvised cords isn’t just illegal; it’s dangerous for line crews and for your own family.

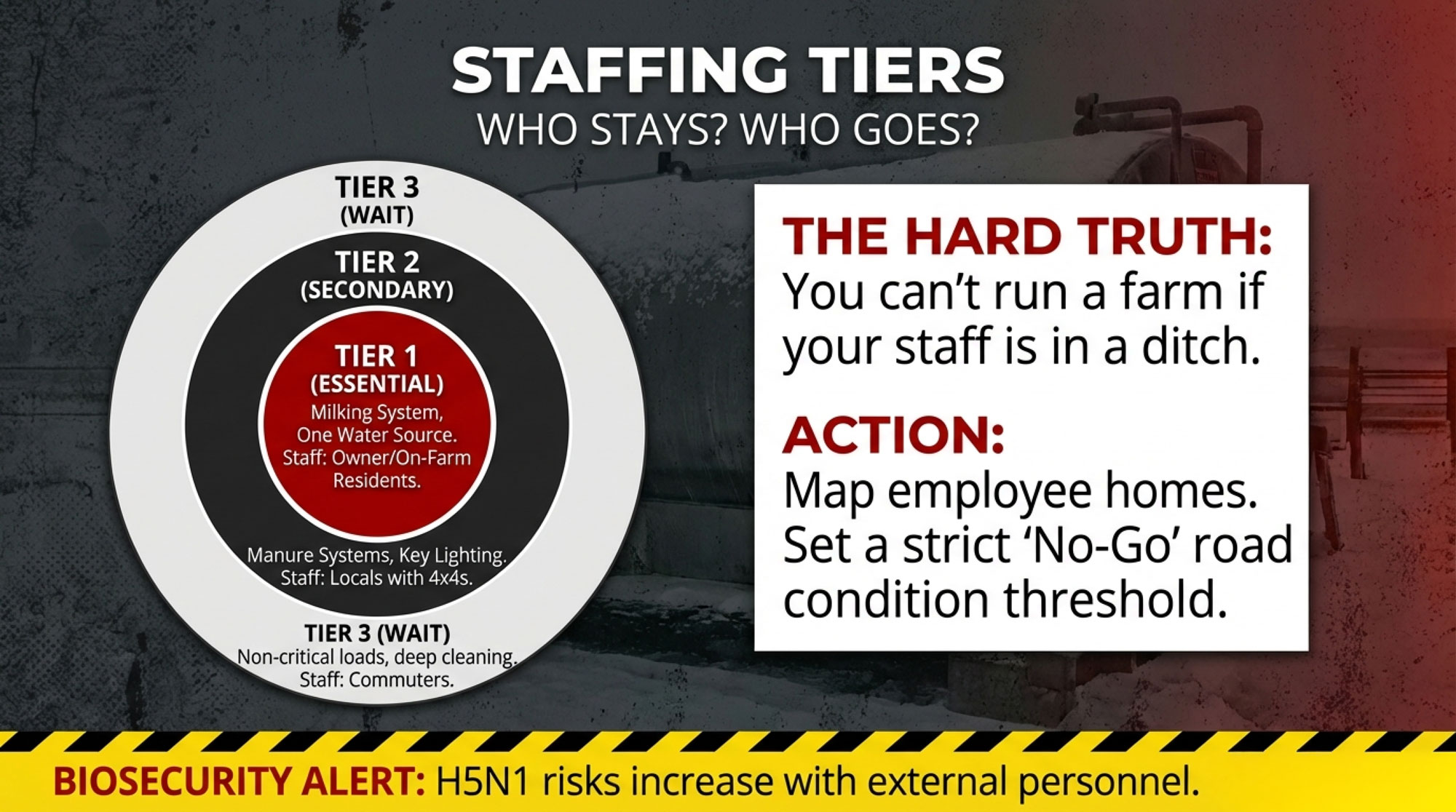

For many small and mid-size herds, especially in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, the practical goal is tiered backup, not full-farm coverage. Farm emergency templates often describe it like this:

- Tier 1: Milking system and one dependable water source.

- Tier 2: Parlor and key alley lighting, one manure system, minimal fans in tight barns.

- Tier 3: Calf housing and non-critical loads, only if capacity allows.

The farms that revisit this after a bad outage usually say the same thing: “We didn’t need everything backed up—we just needed Tier 1 rock-solid and Tier 2 clearly mapped.”

Fuel: How Long Can You Really Keep Running?

Here’s a question worth asking in a quiet moment: “If we had to run this generator almost continuously, how long would our fuel actually last?”

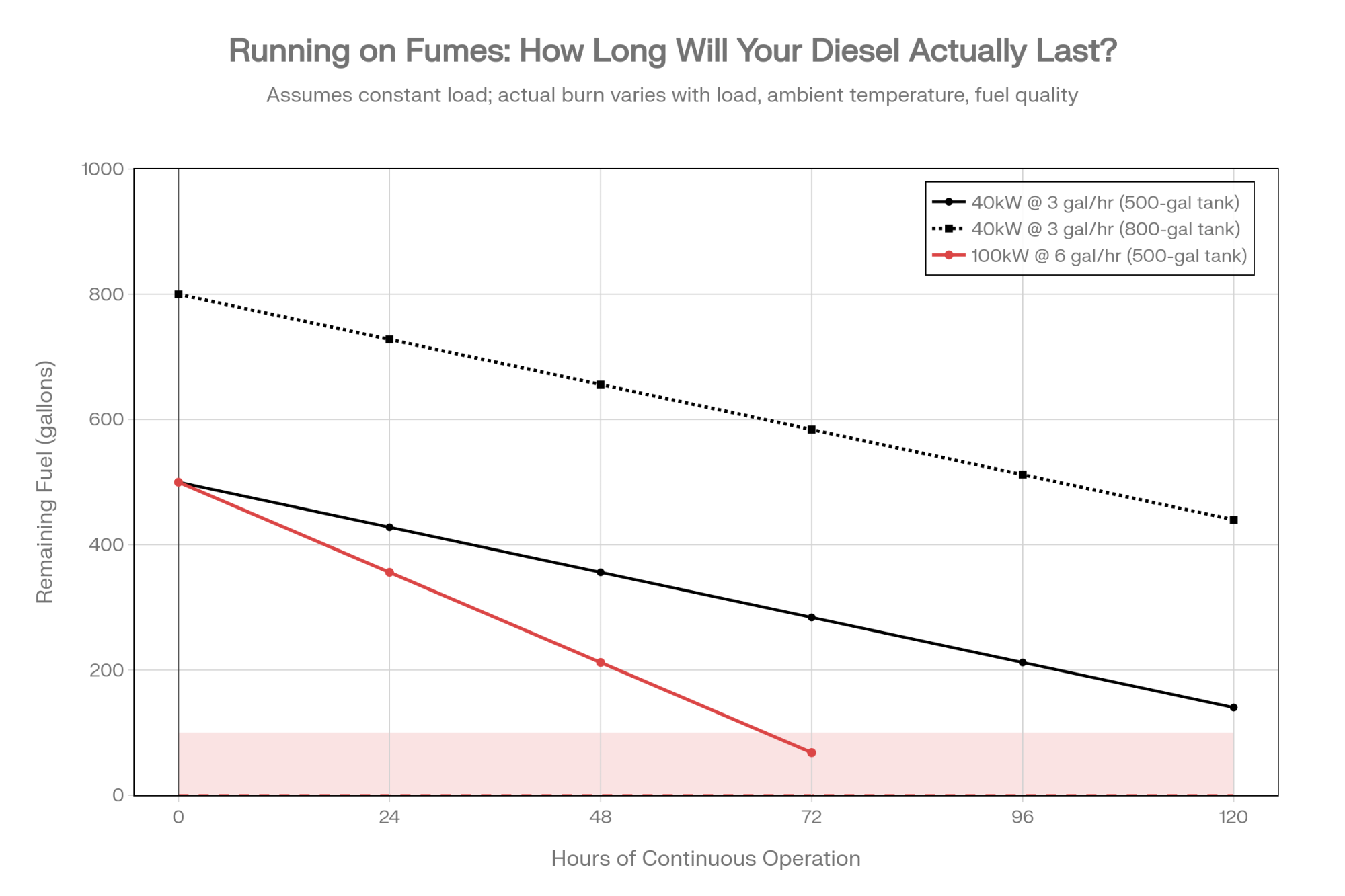

As we covered, a 40 kW diesel set under good load burns about 2–4 gallons an hour; a 100 kW unit typically requires 5–7 gallons an hour. At 3 gal/hour, 72 hours straight is roughly 215 gallons. At 4 dollars per gallon, you’re near 860 dollars in fuel.

| Hours | 40kW @ 3 gal/hr (500-gal tank) | 40kW @ 3 gal/hr (800-gal tank) | 100kW @ 6 gal/hr (500-gal tank) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 500 | 800 | 500 |

| 24 | 428 | 728 | 356 |

| 48 | 356 | 656 | 212 |

| 72 | 284 | 584 | 68 |

| 96 | 212 | 512 | (empty) |

| 120 | 140 | 440 | (empty) |

Cold-climate extensions like NDSU often use a three- to five-day window for worst-case winter planning. Not every farm can or should store five days’ worth of diesel on-site—fire code and risk are real—but knowing you can cover at least three days, and that your supplier has an emergency plan with you, moves you from “wishful thinking” to “managed risk.”

The herds that treat “fuel days on hand” as seriously as “days of feed on the pit” tend to sleep a bit better when the lines start buzzing.

Water: The Other Utility You Can’t Fake

If there’s one thing every dairy nutritionist agrees on, it’s that water drives intake. Penn State’s “Value of Water” bulletin says lactating cows typically drink 30–50 gallons a day, with most of their requirement met through drinking water. And here’s the part that matters for storm planning: cows typically drink 30–50 percent of their daily water within an hour after milking, according to both Penn State and Michigan State. So if your waterers go down right after milking, you’re hitting them at the worst possible time.

For a 2,000-cow freestall herd, using that verified 30–50 gallons per cow per day just for drinking, total daily drinking water needs could range from 60,000 to 100,000 gallons—and that’s before accounting for wash water.

When it comes to water, most resilient farms lean on three basics:

- Keeping lines from freezing. Adequate burial depth for your local frost line, insulation on exposed runs, and self-regulating heat cable on vulnerable sections are all standard recommendations in winter watering guides from Ontario, the Prairies, and northern U.S. states.

- Keeping drinkers ice-free. Heated waterers, sheltered troughs, and constant-flow systems that use ground heat are among the winter advice from the extension offices in Ohio, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Shielding tanks from wind and checking them more frequently can be as important as the hardware itself.

- Having backup supply options. Nurse tanks on running gear, portable troughs, and valves that let you re-route water if a main line or pump fails are common suggestions in Purdue and similar extension resources.

In many Wisconsin and Ontario herds I’ve walked, the operations that ride out January cold best treat water almost like feed: they build in redundancy and know exactly where the weak points are.

48–24 Hours Out: Feed, People, and Communication

Once you’ve shored up power and water as best you can, the next day is really about three levers: how you feed through the cold, who’s actually going to be on site, and whether the right conversations have happened before the snow flies.

Feeding Cows Through Cold Without Trashing the Ration

You probably know this already, but the research backs it up nicely. SDSU Extension’s winter feeding guidance uses the rule of thumb we mentioned: once cattle are below LCT, maintenance energy needs increase by about 1% per degree Fahrenheit. And according to their data, cold-stressed cattle may increase intake anywhere from 2–25 percent if the ration allows it, with the lower end of that range (2–5%) occurring at milder cold (41–59°F), and the upper end (8–25%) kicking in once effective temperatures drop below about 5°F.

So let’s walk through the math. If cows are effectively 18°F below LCT, that guideline implies an additional 18 percentin energy demand. On a 200-cow herd feeding 50 lb/head/day, you might bump to 58–60 lb/head/day for a few days—an extra 1,600–2,000 lb of TMR daily. At 8 cents per lb of dry matter, that’s roughly 128–160 dollars per day. Over three days, call it 400–500 dollars in extra feed.

| Scenario | Extra TMR/Day | 3-Day Cost | Protected Milk Income | Net ROI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do Nothing (18°F below LCT) | 0 lb | $0 | $0 (lose 3–4 lb/cow/day) | –$2,400–$3,200 |

| Modest Bump (5 lb/head/day) | 1,000 lb | $240 | $2,400–$3,200 | +$2,160–$2,960 |

| Aggressive Bump (10 lb/head/day) | 2,000 lb | $480 | $2,400–$3,200 | +$1,920–$2,720 |

| Feed Waste Scenario (20% spoilage) | 1,000 lb | $300 (with waste) | $2,400–$3,200 | +$2,100–$2,900 |

If you avoid losing 3–4 lb of milk per cow per day across that period, you’re protecting roughly 2,400–3,200 dollars of milk. When you see it that way, feeding for the cold isn’t charity—it’s risk management.

What stands out in herds that ride these spells out well is a consistent pattern:

- They consciously bump TMR for high groups during the worst cold—5–10 lb/head/day is common—and then dial back once temperatures normalize.

- Their nutritionist adjusts energy sources, nudging rations toward more digestible forage and carefully managed by-products or fats, while keeping an eye on starch intake so it doesn’t wreck rumen health or butterfat levels.

- They give extra attention to fresh cow management and cow comfort during the transition period, not just in mid-lactation pens, because those cows are already under stress.

On the calf side, calf welfare research and industry pieces in Hoard’s Dairyman note that dairy calves can begin experiencing cold stress at temperatures just below 50°F, especially in damp or drafty housing. That’s why jackets, deep straw packs, and draft control in hutches and calf barns are basically standard from late fall into spring in many Midwest and Northeast herds.

Staff and Family: Who Will Actually Be There?

Talking with producers from Vaughan across Ontario, through Wisconsin, and down into New Mexico, this is often where the conversation turns very real. It’s one thing to say “we all pitch in,” and another to say, “I don’t want my feeder on 45 minutes of black ice at 4 a.m.”

Farm emergency plans in British Columbia and Alberta encourage producers to structure staffing the way they structure power—deliberately and in tiers. Many dairies are doing something like this:

- Identifying one or two core people—often a family member and the lead herdsman or herdswoman—who will be on-farm if conditions demand it.

- Setting clear thresholds—snowfall, ice, visibility, road closures—beyond which staff who live farther away are told to stay home.

- Defining “must do” vs “can wait” tasks, so limited labor can focus on milking, feeding, water, and fresh cows first.

What’s interesting is that when farms communicate this clearly, it tends to build—not erode—trust. People like knowing that their safety matters as much as getting the third milking in.

Communication and Mutual Aid

In the Upper Midwest and eastern Canada, you’re seeing more talk of mutual aid between farms. After big blizzards and ice storms, USDA field staff and co-op reps have noted that herds with pre-storm conversations about sharing capacity—tank space, generator power, even labor—had more options than those trying to negotiate in real time.

Those conversations usually revolve around questions like:

- If a neighbor’s bulk tank fails, can anyone else take a load, subject to the processor’s rules and biosecurity requirements?

- If one generator dies and another farm has spare capacity, is there a safe way to power a well or a small barn temporarily?

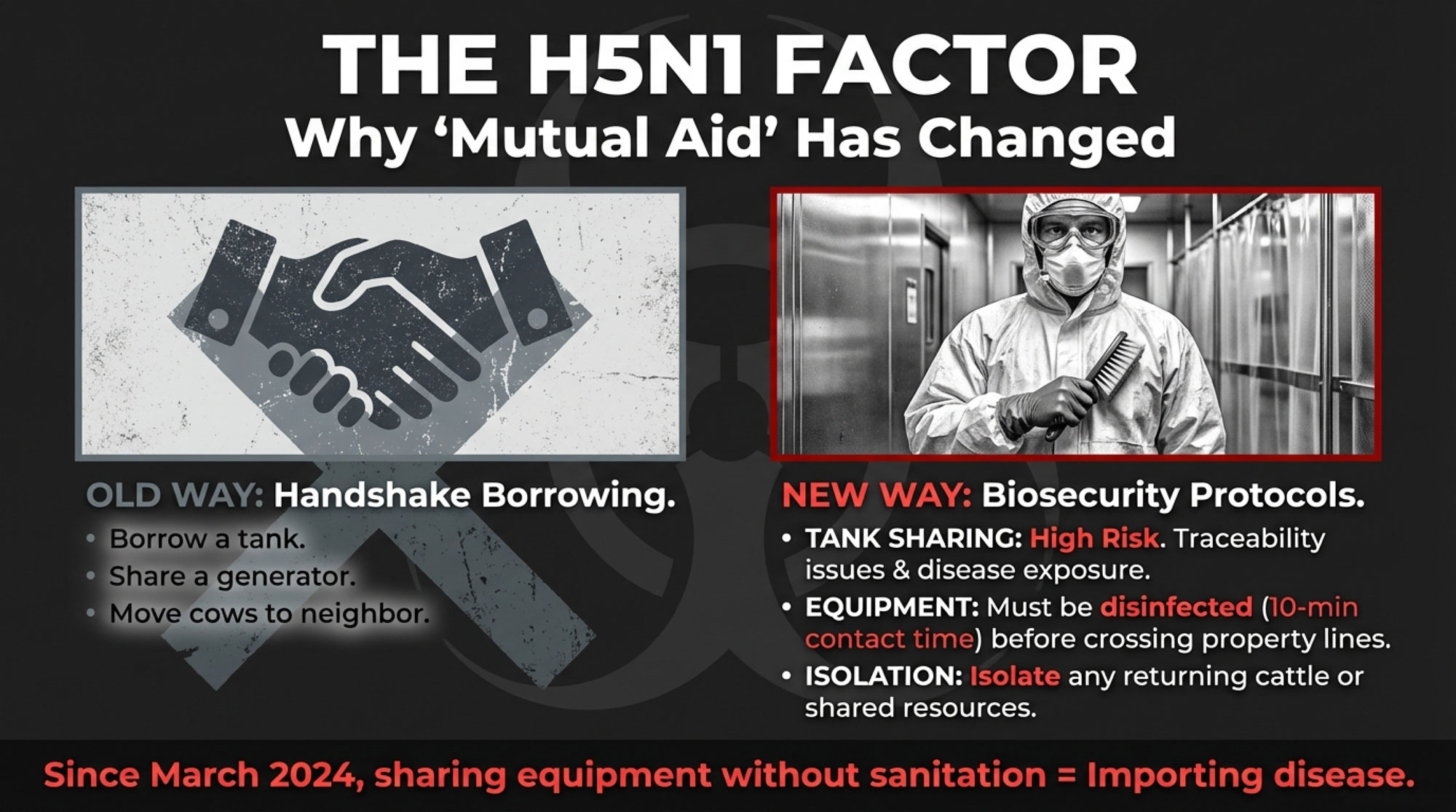

But here’s where things get more complicated in 2025 and 2026—and you probably know where I’m going with this. Biosecurity concerns have intensified dramatically since highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 was first detected in U.S. dairy cattle on March 25, 2024. The CDC confirmed that initial Texas case, and by late 2025, according to Dairy Reporter, the virus had spread to dairy herds across 16 or more states, with California hit particularly hard.

The European Food Safety Authority published a detailed assessment in December 2025, noting that transmission within farms is primarily driven by contaminated milk and milking procedures, while farm-to-farm spread is mainly linked to cattle movement and shared equipment.

What does that mean for mutual aid during a storm? A few practical realities:

- Tank sharing is much trickier now. Mixing milk from different herds—even temporarily—creates traceability headaches and potential exposure to disease. Before you assume a neighbor can take your load, talk to your processor and your state or provincial veterinarian about what’s actually permitted. USDA’s Federal Order, effective April 29, 2024, requires that lactating dairy cattle receive a negative test for Influenza A virus at an approved laboratory before interstate movement.

- Shared equipment is a known risk factor. EFSA’s assessment specifically identifies shared equipment and contact with external personnel as risk factors for between-farm spread of HPAI. If you’re borrowing a loader, a pump, or even a set of milking claws, the expectation now is that equipment gets properly cleaned and disinfected before it crosses property lines—something that’s harder to manage in the middle of a blizzard. If equipment must move between properties, ensure a 10-minute contact time with an EPA-registered disinfectant effective against Influenza A (H5N1) before it touches your driveway.

- Isolation protocols matter more than ever. Biosecurity surveys have consistently found that many U.S. dairy operations lack formal quarantine facilities or protocols for introduced cattle—a gap that USDA and state veterinarians have identified as a significant risk factor for disease spread. The National Milk Producers Federation’s biosecurity guidance recommends isolating newly introduced or returning cattle for at least 30 days and limiting livestock movement. Their guidance also notes potential risk when feeding unpasteurized dairy products to cattle and recommends heat treatment or pasteurization of milk from sick cows to help inactivate H5N1.

None of this means mutual aid is dead—it just means the conversations need to happen earlier and with more detail. When a cluster of farms, their fieldman, and their hauler sit down in November instead of mid-January, and when they explicitly address biosecurity alongside logistics, it turns vague goodwill into usable options that won’t blow up in anyone’s face come spring.

And it’s worth noting that the American Farm Bureau Federation estimates farmers had at least 3.6 billion dollars in uncovered losses across all sectors from 2020 natural disasters alone, and more than 21.4 billion dollars in crop and rangeland losses from 2022 severe weather—losses not fully insured or compensated. Those numbers should make all of us a bit more interested in neighbors, paperwork, and plans—even when the rules around sharing have gotten stricter.

24–0 Hours: Animal Comfort and Final Checks

As the radar colors get louder and the start time firms up, you’re out of the “build new systems” phase and firmly in “put animals where they’ll cope best and tighten the loose ends.”

Understanding Cold Limits in Real Barns

Decades of extension work basically backs up what you already know: a mature cow with a dry winter coat and decent condition can tolerate surprisingly low air temperatures if she’s out of the wind and staying dry. A wet, wind-blasted cow at the same temperature is a different story entirely.

Livestock extension materials often use approximate LCT values around the high teens Fahrenheit for cattle in full winter coat, and much higher thresholds—mid-40s up toward about 59°F—for animals with wet or thin coats. The exact number doesn’t matter as much as the principle: wind and moisture move the goalposts.

From there, your tool kit is familiar but powerful:

- Windbreaks that actually work. Barn walls, shelterbelts, trees, bale stacks, and panel/tarp setups can all reduce wind speed, lowering energy demand and helping cows maintain body condition.

- Deep, dry bedding. Enough straw or stalks so cows can nest and stay off frozen concrete or mud. Producers on both sides of the border report better production and fewer sick cows when they treat bedding like feed during a cold snap.

- Timing higher-energy feeding. Beef work from Kansas State and others has shown benefits from timing higher-energy feeding so peak fermentation and heat production align with the coldest period of the night. Dairy herds with some scheduling flexibility can apply the same concept to TMR delivery.

For calves, the margin is tighter, which is why jackets, deep straw, closing drafts, and sometimes bumping milk solids a bit in prolonged cold show up in calf-management guidance.

A Deliberate Walk-Through Before It Hits

In the last 12–24 hours, a lot of seasoned producers do a slow walk-through that looks a lot like a pre-flight check:

- Start the generator, switch through the transfer switch, and listen and watch as motors start and stop.

- Fill overhead tanks, nurse tanks, and portable troughs so a single pump hiccup doesn’t immediately turn into a water crisis.

- Top up fuel in loaders, skid steers, and tractors so feed doesn’t stop when a machine runs out of fuel.

- Look up at roofs, trees, and attachments near parlors, calf barns, and feed sheds for obvious ice-load or wind risks—something producers in the Northeast and Quebec remember all too well from past ice storms.

More farms are also adding one simple item to that checklist: “How and when are the people staying on-farm going to rest?” When you read post-storm write-ups in regional farm media, a surprising number of costly mistakes come down to fatigue, not a lack of knowledge.

During the Storm: Triage and the Milk That Might Not Move

Once the storm is fully on top of you, you’re not building resilience—you’re deciding what to protect first and what can wait without breaking the operation.

Most farm emergency plans—and a lot of producer stories—in the extension literature boil priorities down roughly like this:

- People first. No extra scraping or third milking is worth a serious injury on ice or under a stressed roof.

- Water and basic feed next. Cows handle dirty alleys better than empty bunks or dry waterers.

- Milking frequency and fresh cows after that. In some storms, temporarily moving from 3x to 2x milking makes sense to protect staff and equipment. That’s a decision to make with your vet and adviser because it affects udder health, production, and butterfat performance.

- Everything else, as conditions allow. Manure handling, bedding changes, and non-critical repairs are “do when it’s safe,” not “do at all costs.”

You can’t be everywhere, so many herds settle into a rhythm: quick checks every couple of hours on generator output, fuel, main waterers, bulk tank temperature, and vulnerable groups (fresh, hospital, calves), plus broader walks every four to six hours to look at feed access, drifting, and overall stress.

And if the milk has nowhere to go?

Uri made the picture painfully clear. Turley’s 1,800 dumped semi-loads in Texas and Sharp’s estimate of 2,000–3,000 dumped loads regionally weren’t projections—they were full tanks washed away. That’s exactly the kind of loss the Milk Loss Program was created to soften.

According to the FSA fact sheet, to claim MLP, you’ll need to file Form FSA-376, supply milk marketing statements from the month before and the month of the loss, and provide a written description of the qualifying event and how it prevented normal marketing.

| Documentation Step | What to Record | FSA Form & Timing | Recovery Rate & Max Claim |

|---|---|---|---|

| During Storm | Date, milking (AM/PM), approx. volume (cwt), reason (no pickup, plant down) | Start notes | Builds MLP claim foundation |

| Milk Dump Log | Dumped milk daily: date, volume, cause (hauler cancel, processor closure) | Keep with farm records | Up to 30 days/year covered |

| Hauler/Processor Notice | Screenshot/save texts/emails from milk hauler and processor explaining disruption | Email or text, saved | Supports “prevented normal marketing” proof |

| Photo Documentation | Photos of generator running (if applicable), drifts blocking milk house, any visible stress or dead stock | Take during event | Visual evidence of qualifying disaster |

| FSA-376 Filing | Milk marketing statements (month before, month of loss); written description of event and impact | File with FSA within 60 days of loss | 75% standard / 90% underserved producers |

| Claim Processing | FSA calculates loss based on milk price (announced price, not spot), volume, and payment tier | FSA review period ~60–90 days | Max claim: 30 days of milk loss per claim year |

| MLP Check Arrives | Payment issued; typically 75–90% of documented loss value | Processed after FSA approval | 75–90% of loss recovered |

So in the middle of the storm, if you’re forced to dump, two small habits make a big difference later:

- Note the date, milking (AM/PM), and approximate volume dumped, plus the reason (no pickup, plant down, no power to tank).

- Save any texts, emails, or written notices from haulers or processors explaining the disruption.

Those details are what convert a five-figure loss from “total write-off” into something MLP can at least partially cover.

After the Storm: Counting the Cost and Closing the Gaps

When the storm passes, and the lights stay on, the instinct is to jump straight into fixing. Some repairs can’t wait. But USDA disaster guidance and provincial emergency manuals keep returning to the same message: document first, then repair when you can.

On the documentation side, that usually means:

- Taking photos of damaged barns, parlors, calf barns, feed sheds, and manure storage from multiple angles.

- Recording equipment failures—generators, pumps, bulk tanks, robots, feeders—with make and model when possible.

- Logging livestock losses with dates, numbers, and veterinary input when available.

- Documenting feed losses—collapsed silage faces, frozen TMR, ruined hay.

- Keeping a simple log of dumped milk: dates, milking times, approximate amounts, and reasons.

Those records are the backbone of claims not only for MLP, but also for the Livestock Indemnity Program (for eligible livestock deaths beyond normal mortality), ELAP (for certain feed and water-related costs), and the Emergency Conservation Program (for land, fence, and structure repair). They also give you numbers you can take to your lender and insurer.

Let’s circle back to the bigger math. That same 200-cow herd dumping a full 7,000-gallon load is losing something like 1,600 cwt of milk. At 20 dollars per cwt, that’s 32,000 dollars in gross revenue. Under MLP, a standard producer might recoup around 75 percent of that, about 24,000 dollars, assuming full eligibility and no caps. That still leaves roughly 8,000 dollars uncovered—and that’s before any building damage, dead cows, or feed spoilage.

The American Farm Bureau Federation’s analysis of 2020 disasters estimated at least 3.6 billion dollars in uncovered farm losses that year, and their 2022 assessment put crop and rangeland losses from severe weather at over 21.4 billion dollars—losses not fully covered by insurance or disaster programs. The takeaway is pretty clear: insurance and disaster programs matter, but they rarely make you whole. Planning and documentation are what turn “disaster” into “serious but survivable.”

Then there’s the debrief. A week or two after the dust settles, when you’re not running purely on adrenaline, is the time to ask with your family or team:

- What worked the way we hoped?

- What failed—or almost failed—and why?

- If this exact storm hit again next winter, what would we want in place before it started?

Sometimes the answers are big—new generator, roof work, major drainage, or windbreak projects. More often, they’re a string of smaller but powerful changes: upping minimum fuel days on hand, adding one more nurse tank, tightening fresh cow protocols when storms are forecast, or agreeing that any dumped milk or unusual death gets logged the same way, every time. Those steady, unglamorous moves are what keep a bad week from becoming a bad year.

Four Decisions That Belong on Every Dairy’s List

So, from a practical standpoint, what moves belong on almost every dairy’s list? I’d argue at least these four:

- Know your generator math.

Work with your electrician to nail down your true Tier-1 load and the cost to back it up properly. Then calculate how many hours or days of fuel you can reliably cover. - Set a simple documentation standard.

Decide that any dumped milk or unusual livestock loss gets a date, volume/count, reason, and a couple of photos recorded the same way every time. That’s your ticket into MLP, LIP, ELAP, and a more intelligent discussion with your lender. - Put your own number on a lost load.

Use your current milk check—price, components, any premiums—and put a real dollar figure on one full lost load for your herd. Write that number at the top of your storm plan. It will change how you view fuel, backup power, and staff rest. - Pick one program to understand truly.

Whether it’s MLP, LIP, ELAP, or the Emergency Conservation Program, spend 10–15 minutes on the phone with your local FSA office or provincial counterpart to clarify how it actually works and what records they need before you ever file a claim.

From Ontario to the Upper Midwest and down into the High Plains, resilience rarely comes from one big, dramatic project. It comes from stacking a series of honest conversations and incremental decisions: a better transfer switch here, an extra tank there, a cleaner staffing plan, a habit of writing things down. That’s how you end up on the right side of the $3.6 billion gap between disaster and survival.

The storms aren’t going away. The cows aren’t going to stop milking. The leverage for all of us, season by season, is making sure the systems and numbers around those cows are just a little more ready each time the sky turns that particular shade of winter grey.

What’s the one piece of equipment—or one decision—that saved you in the last big blow? Drop it in the comments. Whether it was a generator that finally paid for itself, a nurse tank you’d almost sold, or just having the right people on site, your experience might be exactly what another producer needs to hear before the next storm rolls in.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Three days without power = ~$10,000 in dumped milk for a 200-cow herd—before equipment failures or dead animals add to the toll.

- $1,000 in fuel or $10,000 down the drain. A 40 kW generator burns roughly 215 gallons over 72 hours. That’s a 10:1 return you can’t afford to gamble.

- MLP recovers 75-90% of milk losses—but only with paperwork. Document dates, volumes, and reasons as you dump. No records, no payment.

- H5N1 rewrote mutual aid rules. Since March 2024, sharing tanks or equipment carries real biosecurity risk—have those neighbor conversations now, not when the snow’s flying.

- Survival isn’t luck—it’s math. Generator sizing, fuel reserves, water backup, and one simple documentation habit separate a tough week from a devastating year.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Dairy Management in the Face of Adversity: Focus on What You Can Control – Safeguard your margins by mastering the variables within your fence line. This breakdown identifies critical management levers that minimize losses during volatility, ensuring your operation remains profitable regardless of the weather or market shocks hitting your neighbors.

- The Future of Dairy Policy: Navigating Evolving Disaster Support – Arms you with the intelligence needed to navigate shifting federal disaster relief and insurance frameworks. Discover how evolving support structures provide new financial layers of protection, securing your operation’s longevity against increasingly frequent and severe climate events.

- Off-Grid Resilience: Integrating Renewable Energy on the Modern Dairy – Delivers a blueprint for technical and financial independence through on-farm energy production. Explore how solar and biogas integration creates a resilient safety net, eliminating grid dependency while slashing long-term overhead and boosting your farm’s sustainability profile.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!